The Real War on Crime:

The Real War on Crime:

The Report of the National

Criminal Justice Commission

Steven R. Donziger, Editor,

HarperPerrenial, 1996

Reviewed by C.R. BARON

n 1764 Cesare Beccaria, a young lawyer and recent graduate of the University of Pavia, made history with the publication of his Crimes and Punishments, a revolutionary treatise on criminal justice. Inspired by Enlightenment philosophies and against a backdrop of barbaric practices, Beccaria’s ideas marked a major advance in criminological thought. His book enjoyed instant success in Europe, its influence eventually making its way across the Atlantic into the legislation of several American states.

Two hundred and thirty two years later in 1996, Steven Donziger, a young lawyer and recent graduate of Harvard University, published The Real War on Crime, a 300-odd page volume that promises to provide a “comprehensive assessment of crime policy in America, to offer solutions to reduce violence... and to determine if the ‘war on crime’ has been effective.” Edited by Donziger, The Real War on Crime is the collective report of the National Criminal Justice Commission, a privately funded group of 34 prosecutors, police chiefs, defense attorneys, academics, and other concerned citizens who came together in early 1994 for the two year project. The book’s promise to supply a large dose of reality to remedy the distorted impressions of a sensationalist media is a worthy goal and welcome to a readership hungry for what’s actually going on. The report succeeds in painting that reality, sometimes in striking display, but the total picture it presents looks incomplete.

In spite of this, selected portions are alive and vibrant, each one valid as a stand-alone subject. In essence, The Real War on Crime is a masterpiece that could have been—and might have, had Beccaria’s thin volume been consulted. But it was not, and the result is a mixed bag.

The report opens just that way with a litany of “facts” both resonant and dissonant. Here is a sampling taken from Donziger’s preface in which he summarizes the findings of the Commission:

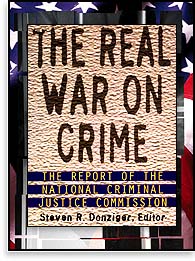

So, in its first two pages The Real War on Crime manages to set a difficult tone, a tone that improves only marginally as it launches into its subject. With the “exploding prison population” we are led directly to the report’s main theme: Our governments have poured billions into new prisons, passed any number of tough new crime bills, have imprisoned convicted offenders at unprecedented rates—tripling the prison population between 1980 and 1994—and all for little or no effect on crime rates. As taxpayers, we have not gotten our money’s worth; we’ve been the victims of a hoax, is the hue and cry of The Real War on Crime. That our criminal justice system today is ineffective is the major thread weaving throughout the report, yet crime rates have in fact been dropping steadily for four or five years. Since 1992-93, they have fallen nationwide, plunging dramatically in 1995 and 1996, and with spectacular successes in some cities like New York, Boston, and San Diego. While several plausible reasons have been advanced to explain the decline, some experts believe it is the direct result of putting more criminals in prison and keeping them there longer.

| ||

|

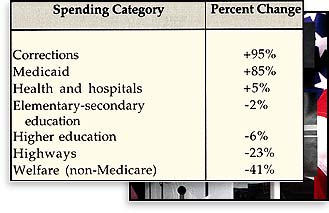

The Commission’s conclusions are punctuated by numerous charts and graphs, most telling us that we are spending more and more money with relatively little result. |  |

From the point of view of policy, anti-crime initiatives and such, what causes crime rates to rise and fall is the subject of serious contention and fierce debate among experts and lay persons alike. To stay above the fray, yet acquire some perspective, it is worth harking back 200 years to Beccaria’s book for a brief consultation. Beccaria argued two major points and minced no words in the telling:

1. The effectiveness of criminal justice depends largely on the certainty of punishment, not its severity;

2. The proper objective of the penal system is to devise penalties only severe enough to ensure public order and safety and anything in excess is tyranny.

As guidelines, Beccaria’s principles are at once sane, embracive, non-ideological. Naturally, the business of putting convicted criminals in prison and having prisons to put them in bear directly on certainty of punishment and the effectiveness of criminal justice, a large point that seems to have escaped Donziger et al. With these omissions, Real War virtually ignores 50% of that which, according to Beccaria, constitutes effective criminal justice. Comprehensiveness, we are forced to conclude, is not its strong suit.

However, in covering Beccaria’s second point, the severity of punishment, the report succeeds famously and indeed covers that territory with thoroughness. It describes the wide panorama of evils that have attended the mad rush to imprison our fellow citizens: the skyrocketing costs, the enormous strain on our social fabric, and the distortions created within the criminal justice system itself.

To begin with, the numbers themselves are staggering. In 1995 more than 1.5 million Americans were behind bars, three times as many as in 1980. The U.S. imprisons 555 out of every 100,000 citizens, a rate five times that of Canada or Australia, and seven times most European democracies, while the crime rates in those countries are virtually identical to ours (with the exception of homicide). In addition to the 1.5 million behind bars, there are another 3.6 million on probation and parole, for a total of over 5 million people, almost 3% of the adult U.S. population. For African-Americans that figure surges by an order of magnitude to 33%. One out of three African-American males aged 18 to 34, today live under the supervision of our criminal justice system, either behind bars, on probation, out on bail, etc. While this incarceration may move us in the direction of certainty of punishment it is by no means a done deal nor a fair deal. Should anyone be tempted to applaud, consider this: that fully 84% of the 1 million prisoners added since 1980 were convicted of non-violent offenses, many drug-related. And, if you’re thinking that at least the violent criminals are being kept off the streets, consider this: in 1992, federal prisons held 1,800 murderers who were serving an average time of 4.5 years while 12,727 non-violent first time drug offenders were serving an average sentence of 4.5 years.

| ||

|

84% of the 1 million prisoners added since 1980 were convicted of non-violent offenses. If all 50 states were to fully implement all of the get-tough measures that now only some have adopted, the prison population would soon rise to 7.5 million at an annual cost of $221 billion. |  |

A study by the National Council on Crime & Delinquency predicts that, if all 50 states were to fully implement all of the get-tough measures that now only some have adopted, the prison population would soon rise to 7.5 million at an annual cost of $221 billion—compare the total 1995 U.S. defense budget at $269 billion! Some other eye openers: The cost to operate and maintain a single prison cell in the U.S. runs taxpayers anywhere from $22,000 to $30,000 annually; the cost to build that cell, including debt service, a cool $100,000. Each elderly prisoner (55 and above) costs us $69,000 per year. (Of note, but not addressed in Real War, is that certain criminal rehabilitation programs run by private charitable institutions cost next to nothing and yet yield striking results; by way of example, Criminon costs approximately $170 per prisoner over a three to twelve month period, and in one site where it was employed, recidivism dropped from 80% to 10%.)

In 1991, American cities spent more money on the criminal justice system than education. At the state level nationwide, for the years 1976-1989, spending on “corrections” increased 95% while elementary/ secondary and higher education decreased by 2% and 6%, respectively. Yet probation and parole programs have remained woefully underfunded. The average caseload for a single probation officer, considered optimum at 30, now stands at 200 plus. The sheer volume alone prevents case officers from doing anything but the most cursory supervision. The primary purpose of probation has also changed substantially over the past 20 years: it used to be rehabilitation, now it focuses almost exclusively on technical violations and putting violators back into prison.

On the social front, the report presents compelling evidence of racial and ethnic discrimination throughout the criminal justice system. On average, Native Americans, Hispanics, and African-Americans receive harsher treatment at every step of the criminal justice process. Compared to whites with comparable criminal histories, minority offenders are arrested at higher rates, charged by prosecutors with a more serious crime for the same offense, are released less often before trial, pay more money for bail, receive significantly worse deals in plea bargaining, and get longer sentences. While there are many individual exceptions and while the bias at any one step may be small, the cumulative effect results in a far greater percentage of minority offenders in prison than white. For instance, though African-Americans use illegal drugs at roughly the same rate as whites, 74% of those sent to prison for drug possession are African-American.

The Real War on Crime concludes with a number of sound recommendations, several of which have already been put into effect to varying degrees in various locales. One calls for restoring the balance of power between judges and prosecutors that was destroyed in favor of prosecutors, particularly as a result of three strikes laws. In April, 1997, the California Supreme Court ruled that in three-strikes cases, judges may, at their own discretion, re-categorize as misdemeanors the crime before them or either of the prior two felonies. This is welcome news to an inmate now serving 25 years for his three felonies, one of which was for stealing a slice of pizza.

Perhaps the report’s most important recommendation from the perspective of crime policy is the call for an independent body commissioned by Congress to act as a clearinghouse for accurate and comprehensive criminal justice information grounded in results—the only sane basis for policy making. Independence from other organs of government is urged because lying with statistics is a regular indulgence for ideological hobby-horsers and vested interests. In the report, the Justice Department, the media, the N.R.A. and others take a sound trouncing for skewing statistics to serve their own narrow purposes. (Even Real War itself is not immune to this lapse.) Impartial and proactive, such an independent body would be responsible not only for gathering statistics but for establishing standards in reporting statistics and for providing hard-to-get information about the hundreds of criminal justice related programs that community groups, religious groups, and police departments are engaged in. Some are notably successful and important to other communities struggling with the same problems. Yet no institution currently exists for gathering and disseminating such information.

While the root causes of crime lie at the periphery of the report’s stated scope, it does venture into that territory with one recommendation: the reduction of poverty. That poverty and crime are inextricably linked is readily acknowledged by most. But the nature of that link has thus far resisted convincing explanation. It is not a cause and effect relationship, for the majority of the poor do not turn to a life of crime. It’s a safe assumption that a number of pernicious influences precede the personal decision to commit crime and poverty is only one such influence, and probably not the most important one. In fact, another influence has emerged recently to take the spotlight: illiteracy. A study by the National Institute of Justice, the research arm of the Justice Department, intelligently suggests that illiteracy is a primary cause of crime. The vast majority of criminals, it found, cannot read and write. This amounts to a key finding for illiteracy underlies poverty as well as crime, and presents an opportunity for resolving both. Illiteracy is not mentioned among the findings of Real War, nor literacy and education among its recommendations, again a large omission. It’s specific anti-poverty recommendations, however, include job training and the creation of employment opportunities in inner-city neighborhoods. Yet all such opportunities would require some degree of literacy. Literacy is factually a vital prerequisite to any kind of viable economic future for anyone in today’s world and effective literacy programs deserve support at all levels of government.

A message implied by the report is that the problems of crime are complex, both in terms of its prevention and its administration by the criminal justice system. This means that there is no single answer. Resolving them requires a simultaneous approach on several fronts and The Real War on Crime suggests eleven in its concluding recommendations. Bringing sanity to the area also requires that policy-makers step back and acknowledge this complexity, renounce a one-size-fits-all solution, and permit some light to enter the heated debate.

Unfortunately, crime policy in the United States has all to often been driven by the heat of passion, mirroring in grotesque parody the passion of the criminal act itself. Such perpetrators of policy are, on the one side, the vengeance-seeking politicos wielding the hand of retribution and, on the other, the do-gooder politicos seeking to restrain that hand. Embroiled, the one cannot understand the other. Standing hard by their respective convictions, neither see that the complexity of crime won’t surrender to reductionist approaches. Consequently, depending on which politicos have the temporary upper hand, crime policy alternates between “tough” one decade and “lenient” the next. What our society needs is the balance Beccaria calls for: Lock ‘em up for sure, but keep the key handy. In practical terms: Adopt effective in-prison programs that teach inmates how to read and write, programs that restore moral values, programs that detoxify bodies to eliminate the craving for drugs and show them alternatives. Then, let ‘em out. In the inner cities, adopt similar programs, always with an eye for what works and what doesn’t.

Uncorrected, the tyrannies of our current criminal justice system that The Real War on Crime so fervently describes will inevitably rebound on all of us, guaranteeing high recidivism and an out-of-control spiral of more crime and more prisons. It will bankrupt us: financially, socially,