CRIMINON Criminal Rehabilitation Program — The Road to Self-Respect

by Steven F. Ayre and Gail M. Armstrong

With prison recidivism rates at 60 percent, the country has long since passed the point of needing effective solutions. Freedom examines one program achieving results.

etween 1952 and 1996, Rudy Owens moved in and out of correctional institutions 16 or 17 times—at some point he stopped counting.

Owens’ revolving-door life began as a familiar story. Growing up in the section of Washington, D.C., known then as the “Badlands”, he was in trouble by the age of 9 when he had his first stay in a juvenile facility.

When most teenagers at age 17 graduated high school, Owens graduated from juvenile to adult offender. The streets, abusing drugs, stealing and other crime, were his life.

| ||

|

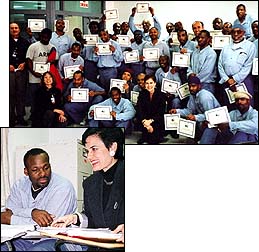

CRIMINON D.C. DIRECTOR Dagmar Papaheraklis (at left and top, front center) and volunteers have helped more than 500 inmates in Lorton, Virginia, graduate from the program. |  |

With his repeated returns to juvenile centers and prisons, Owens personified a corrections system that has become a stranger to its original mission to correct and rehabilitate offenders. He also seemed to prove the notion that criminals are incorrigible or even genetically destined for lives of crime.

Since the 1960s, the number of “Rudy Owens” who cycle in and out of prisons in the United States has quadrupled.

The parade of alternative programs and methods to reduce recidivism tried over recent decades have met with varying degrees of success. Those that have channeled prisoners into community mental health centers and the drug-based treatment they provide have been documented to actually increase recidivism. (See cover story.) Programs which seek to restore time-honored values of morals and ethics—such as restorative justice programs that require amends to crime victims—have met with some success.

Fortunately for Owens, he came across the Criminon program, proven to reduce recidivism. He has been living a clean and honest life out of prison for a year.

|

Volunteer Efforts

Criminon was first established in New Zealand in 1972 as an outgrowth of the Narconon drug rehabilitation program. Both programs use exclusively the works of American author and humanitarian

Mr. Hubbard, who worked as a Special Officer for the Los Angeles Police Department in the late 1940s, found that every criminal career began with the loss of self-respect, and that individuals only became a real threat to society when they lose trust in themselves.

| ||

|

|

Criminon operates both correspondence courses for prisoners—such as those ongoing in 1,400 prisons across the United States—and on-site programs, which vary in their offerings depending on the needs of inmates and the resources of prisons and Criminon volunteers. Most on-site programs consist of a series of study courses and exercises, like the one attended by Rudy Owens in Virginia.

Support from Inmates

The program at Lorton followed the history of most on-site Criminon programs, which build on results. It began in 1996 in the women’s section of the prison complex’s minimum security facility. Ten inmates were the first to graduate from a series of three courses designed to improve communication and learning skills and help them build a moral foundation—in which they know for themselves the difference between right and wrong, and so make their own ethical decisions in life. The latter part of the program utilized The Way to Happiness, a non-religious, common sense moral code that, with more than 57 million copies distributed in 22 languages since 1981, has seen success with people of all ages and walks of life throughout the world.

The program extended to prisoners in the male minimum-security facility. After demonstrating success there, it moved on to the male, medium-security units.

More than 500 inmates at Lorton completed the program, which takes an average of six or seven months. Criminon volunteers also started to deliver the courses in the first of six planned halfway houses in the Washington, D.C., area.

One distinct aspect of the Criminon program is the support it generates not just from correctional staff, but from prisoners themselves. Even participating in a small part of the Criminon program can produce marked improvements.

“I’ve seen amazing things inside institutions with Criminon,” Owens said. “I’ve actually seen men voluntarily rip themselves away from TV programs to not miss their time [on the Criminon program]. You know the program is working when you see that,” he said. “If the volunteers were late for some reason, the inmates would get mad, like ‘What’s going on?’ ”

Owens described how prison officials and employees would come by the Criminon program to find out what they were teaching. “Men who’d been renegades all their lives were changing. You could see the administrators just wondering, ‘What are you all doing in there?’ ”

Restoring self-respect

The biggest changes on the program come when “inmates realize that deep down, they’re good people but they’ve made some really bad decisions in their lives,” said Dagmar Papaheraklis, director of the Criminon program in Washington, D.C., who works with inmates along with her husband, George, and a network of volunteers. “They regain a sense of right and wrong, and know they can change for real. They start trusting and respecting themselves again.”

Owens experienced fundamental, life-changing results on the program that changed him as a person—his system of values, his outlook, and his choices in life.

“The reason why Criminon is so successful is because of the new approach to everyday life. It’s all about living life on life’s terms,” he said. “You begin to see there is something better than living the way you have been.”

| ||

|

“The success of [Criminon] so far has been remarkable.... The judges assign all the worst and toughest cases to Criminon for an obvious reason: Criminon gets results.” – Judge Heinrich Moldenhauer Chief Magistrate, Pretoria, South Africa |  |

“The program has been so profound in my life. It really changed me. I had a really good look at myself and what I was doing to me. Criminon empowers you to make choices—the right choices—in your life. There is nothing I can say, or even begin to, about Criminon that hasn’t been beneficial,” he said.

Since getting out of prison, Owens has held down regular jobs, and he has been in the process of getting a new job to work with handicapped children. Owens also regularly volunteers time with the Criminon program in D.C., where he is working with the Papaheraklises to establish programs in halfway houses.

“I felt inspiration in myself to give back to the community, after all Criminon had done for me,” he said. His reaction was not isolated. “What’s amazing, is all these men changed their lives. They came back into the community. I see [Criminon] graduates every day out there, working with drug programs, working in halfway houses. Some of them are down at the mayor’s office working with them. They’re giving back to the community.”

“A Great Change”

Fifteen-year corrections veteran Noble Ihezue, who supervised one inmate who was on the Criminon program before parole, now manages halfway houses in Washington, D.C., for the federal government. “We’re using every conceivable means, including the Criminon program, to tackle the skyrocketing crime,” he said. “It’s starting to come under control.”

Noble ran another program in 1992 that was neither very successful nor popular with inmates. It created no change he could measure, despite having 15 staff working on it. After that, he had problems persuading inmates to be involved in any rehabilitation program.

“Criminon represented a great change because you could tell something was happening to the people who went through the program,” said Noble, “and that was with just two volunteers running it at a time. This is the only program all the inmates felt good about.”

Noble says that even now, offenders under his care repeatedly ask him to introduce Criminon into halfway houses. “If they’re saying ‘we need this program here,’ then you know absolutely there’s something good about it,” he said. “The Criminon program should be introduced into the whole criminal justice system. We need to use anything positive that anybody can contribute to change the way we deal with offenders.”

Foundation for a New Life

Another former inmate who completed the Criminon program in Virginia is Lamont Bobbitt, who served eight years for, as he puts it, “being a knucklehead in the streets, without any sense of direction.”

Bobbitt said the Criminon program gave him “that sense of direction and the idea that I was somebody. It taught me the basics about life I’d neglected. When I got home, it was with the decision to be a husband and a father. I’d built the foundation for a new life.”

Since his release, Bobbitt has held steady employment as a quality assurance technician, and has received three promotions. “I love the work, and I’ve been keeping food on the table for over two years now,” he said.

Still on parole, Bobbitt is firm in his conviction that nothing can affect his own growth or erode the foundation he has built for himself. “There’s no going back for me. I’ll continue to work hard.”

Bobbitt attends church each Sunday and is arranging time to volunteer with the church’s basketball tournament because, he said, “I want to work with kids. They’re in turmoil right now and I want to do something to help because I understand what they’re going through.”

That understanding permeates the relationship Bobbitt has with his own three daughters, who he said now find their father concerned about their needs rather than just his own. “In the old days,” he said, “I was just mad at them for no reason.”

Bobbitt credits the Criminon program with his reformation and his new life. “Dagmar and George were there for me and I love them to death for it, so now it’s my turn to be there for others.”

| ||

|

“I’m actually in awe of the results [Criminon] gets. [The inmate students] go from bad to excellent in their actions, their respect for fellow inmates and their correctional officers.” – Betty Nichols, Correctional Officer |  |

Utilizing All Resources

The results among inmates add to the continually mounting evidence of the Criminon program’s effectiveness, and demand for what it has to offer.

Formal studies are in progress to confirm initial recidivism rates of ten percent or less reported by correctional and justice officials connected with the program.

“The rehabilitative technology employed by Criminon will someday soon be utilized by prison systems worldwide, as such methods represent the only truly workable means to handle the increasingly burdensome criminal populations,” wrote Robert F. Henderson of the Queensboro Correctional Facility of New York.

Such responses are echoed throughout the world.

Thousands of miles from the United States, for example, Judge Heinrich W. Moldenhauer, a chief magistrate who presides over 39 judges and 55 courts in South Africa’s capital city of Pretoria, has experienced Criminon’s effectiveness.

After just several months of the program operating, the magistrate wrote, “The success of the programme so far has been remarkable. ... [T]he workload of the juvenile court has dropped from 30 cases per month to just 2, the rest were successfully diverted away from the criminal justice system.”

In fact, in the center of Judge Moldenhauer’s courthouse can now be found a Criminon center where, he said, “we reconverted jail cells into classrooms especially for Criminon. The judges assign all the worst and toughest cases to Criminon for an obvious reason: Criminon gets results.”

Judge Moldenhauer presented Criminon officials in 2000 with a letter signed by the Minister of Justice of South Africa commenting on the enormous impact that Criminon has played in rehabilitation.

“[T]his program is so important to us—and to the world,” Judge Moldenhauer said, “that we’ve brought it to the direct attention of the United Nations so that every courthouse in the world may benefit.”

Combining Strengths

Tammy Terrenzi, president of Criminon International, is intent on making results available to all prisoners, and on working with other recidivism-reduction efforts to reach that goal.

Terrenzi’s decision to make the Criminon program her life’s work was influenced by the experience of her twin brother, once a Los Angeles gang member, drug dealer and addict. He has now been drug and crime-free for eight years and is working as a superintendent for one of the largest construction companies in California.

“I knew there were many others out there like him, either behind bars or about to be,” she said. “We just need to combine the strengths of the effective programs out there and reach them.”

For more information contact Criminon D.C., P.O. Box 53132, Washington, D.C. 20009-3132; (202) 581-7070.See also feature story on Narconon, Freedom Vol 32 Issue 1, available at www.freedommag.org or on request from Freedom.