This account was how Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist working for Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel, described his terrifying experiences after intentionally ingesting what he mistakenly thought was a safe, small amount of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), when it was in fact a strong dose. It was April 19, 1943—five years after he became the first person to synthesize the drug.

Today, despite LSD’s nightmarish effects, this powerful, mind-altering drug is one of the key substances touted as “psychedelics.” These drugs are the focus of renewed clinical investigations in a field that...has taken on the appearance of a fad-like New Age movement with its propaganda spreading across society like a powerful meme.

“I was overcome by the fear that I was going out of my mind, and the worst part of it was, I was clearly aware of my condition,” Hofmann told the medical journalist Margaret Krieg. “I could do nothing to prevent the breakdown of the world around me. I had a feeling as if I were out of my body. I thought that I had died…I even saw my dead body lying on the sofa.”

Today, despite LSD’s nightmarish effects, this powerful, mind-altering drug is one of the key substances touted as “psychedelics.” These drugs are the focus of renewed clinical investigations in a field that, although branded as “psychedelic medicine,” has taken on the appearance of a fad-like New Age movement with its propaganda spreading across society like a powerful meme.

A crucial aspect of the new psychedelics push is that they are pitched in conjunction with mental maladies. Purportedly aimed at tackling an ever-expanding list of problems, particularly among “treatment-resistant” populations, psychedelics are promoted as a panacea for everything from eating disorders, addiction and depression to anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and the so-called “end of life” issues often associated with terminal illness.

The publicity campaign is everywhere. A May 2023 episode of the Dr. Phil talk show started by presenting a CBS News clip with the announcer intoning: “A new clinical study finds that a single dose of psychedelic mushrooms along with talk therapy can be used to treat depression.” The clip went on to feature a woman identified as Tracy T., the founder of Moms on Mushrooms, a Denver, Colorado-based online community where “moms who are struggling with their mental health share stories about how and why tiny amounts of psilocybin [the active ingredient in magic mushrooms] called microdoses can help.”

“Watching some of this backstage right now reminds me why we have 120,000 deaths a year from drugs in this country. This drug culture, where we just want to just grab the next magic silver bullet to help us with real traumas, I think is really troubling.”

On the Dr. Phil show, entitled “Moms on Mushrooms: A Growing Trend?” Tracy said she started microdosing on 100-milligram capsules of ground magic mushrooms up to three times a week at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, soon after she lost her business and was “reeling in a lot of grief, a lot of uncertainty.”

Although Dr. Phil emphatically—and correctly—reminded viewers that “empirically there’s no sound, reliable, broad base of research” that suggests psychedelics are helpful, Tracy insisted that her microdosing regimen “has really helped me listen to my body” and that she went so far as to tell her 12-year-old daughter “what microdosing is, what psilocybin is—she knows what the mushrooms look like.”

Kevin Sabet, a former drug policy adviser in the Obama administration, who was also a guest on the Dr. Phil show, denounced the use and propagation of psychedelics as promoted by Tracy. “Watching some of this backstage right now reminds me why we have 120,000 deaths a year from drugs in this country,” he said. “This drug culture, where we just want to just grab the next magic silver bullet to help us with real traumas, I think is really troubling.”

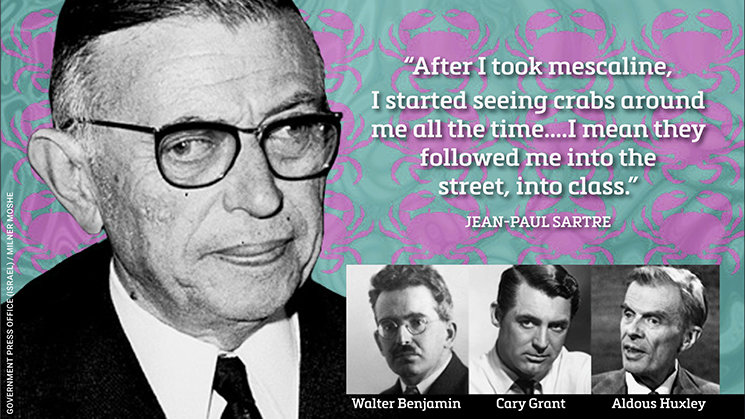

The term “psychedelic” was coined in the 1950s by Humphry Osmond, a British-born psychiatrist in Canada who was exploring methods to cure alcoholism. The root of the word is Greek for “mind-manifesting,” a clever term that seeks to differentiate psychedelics from hallucinogens by suggesting that psychedelic compounds aid in revealing information that would otherwise remain trapped in the subconscious mind. But because hallucinogens, by definition, induce perceptions of sights, sounds or smells not normally present, it should come as no surprise that the two terms overlap considerably.

Acknowledging that psychedelics produce hallucinations and mood or cognitive changes...the FDA classifies the substances in its most high-risk category of “Schedule I” drugs, which are subject to stringent regulatory controls under the 1970 Controlled Substances Act. Because of their “high abuse potential,” the document points out, psychedelics do not have any accepted medical use in the U.S.

Psychedelics are among the most potent, naturally occurring psychoactive substances humans have consumed for millennia in many cultures.

Yet, despite their long history, it wasn’t until the 1940s and 1950s that psychedelics gained prominence after chemists succeeded in extracting or synthesizing a range of compounds, including LSD. And with that, researchers decided to explore how infinitesimal doses of the compounds might affect consciousness and the human brain.

Following the passing of legislation in June 2023 to decriminalize psychedelic mushroom use, the Division of Psychiatry in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a set of guidelines for clinical investigations into psychedelics to facilitate what is predicted to be a multibillion-dollar industry of institutions and organizations researching and advocating for the therapeutic use of the drugs.

The release of those FDA guidelines coincided with a gathering of 10,000 attendees and numerous exhibitors in Denver at a “Psychedelic Science” conference billed as the informal launch celebration of an industry valued in the billions and hyped to “revolutionize” the world of mental health.

The guidelines define psychedelics as an umbrella term that typically includes psilocybin and LSD, along with methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), a recreational drug initially developed in 1912 and better known as ecstasy.

Psychedelics are drugs and as such they are essentially poisons. [Like psychiatric drugs] they provide no more than a temporary escape from life’s problems, while reducing the taker’s natural resilience and ability to deal with those problems.

Acknowledging that psychedelics produce hallucinations and mood or cognitive changes, the guidelines warn that the FDA classifies the substances in its most high-risk category of “Schedule I” drugs, which are subject to stringent regulatory controls under the 1970 Controlled Substances Act. Because of their “high abuse potential,” the document points out, psychedelics do not have any accepted medical use in the U.S.

The advocates of psychedelics—assorted physicians, entrepreneurs and celebrities but in the main, hard-driving psychiatrists, the proponents of the so-called “human potential movement”—claim that despite their potential dangers, the drugs show promising signs of efficacy in treating a range of mental disorders.

Clinical and anecdotal evidence says otherwise—ask any aging boomer who today has terrifying flashbacks of bad trips from the 1960s. More truthfully, the “promising” signs are that these drugs will be profitable—in the extreme.

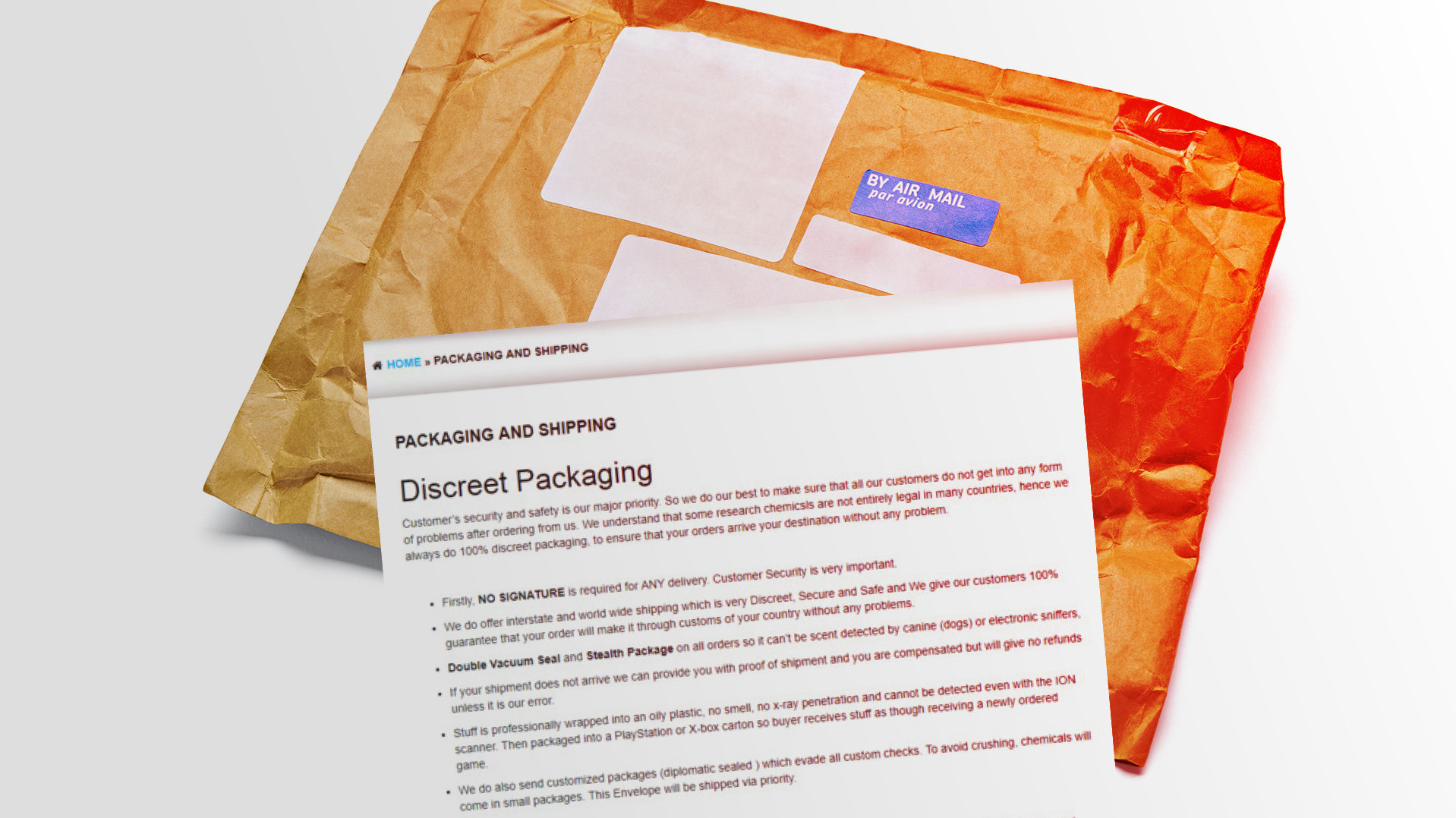

Accordingly, the public is inundated with articles, clinical reports, sponsored events and books on the wonders of psychedelics—all part of an aggressive drug promotion marketing mill.

From a famous actress admitting on a late-night cable talk show on Bravo TV to taking “mushrooms,” to an article in Psychology Today unabashedly promoting “shrooms,” glibly titled “Magic Mushrooms: Where Nature Meets Nurture Within Us” and authored by a psychologist who claims her mission is to “help heal centuries of toxic conditioning that has led America to be one of the most repressed countries in the world.” She provides no evidence or context for her sweeping diagnosis of repression. The truth is, it’s just hype.

Psychedelics are drugs and as such they are essentially poisons.

In scientific medicine, drug uses are tested and proven to treat, prevent or cure disease or improve health. Not so with psychiatric drugs. At best, they only suppress symptoms—symptoms that return once the drug wears off. They provide no more than a temporary escape from life’s problems, while reducing the taker’s natural resilience and ability to deal with those problems. Not to mention the horrific effects of some psychotropic drugs—severe mental and physical reactions, including violence, suicidal ideation and suicide.

The same applies to psychedelic drugs.

Far from heralding a new age of mental health, psychedelics carry their own threat to sanity and are a harmful throwback. Their long-term, widespread use has been disastrous to entire generations.

The future of psychedelics promises nothing more.

The series continues with Part II: The Psychedelics Bandwagon: Down the Rabbit Hole.