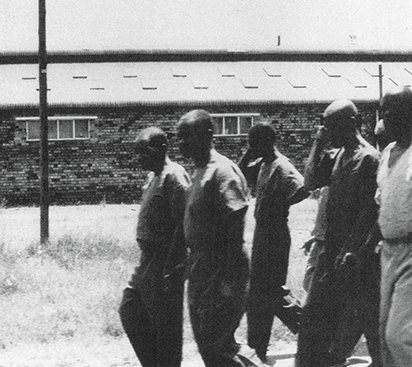

During the height of apartheid, a South African windowpane salesman became lost while traveling through a region pockmarked by abandoned mines. Seeking directions, he stopped at an old mining compound, where he witnessed a troubling sight: a naked woman racing from the compound’s offices, pursued by people in uniform.

The salesman reported the episode to an independent journal in Johannesburg, which began an investigation.

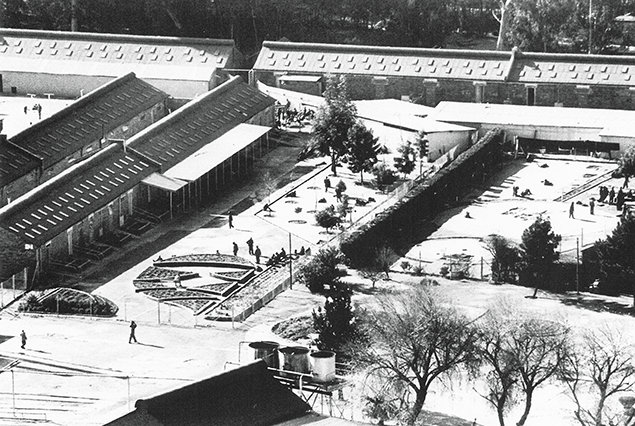

What that journal—the South African edition of Freedom—uncovered was startling. The run-down, forlorn facility the salesman saw had been converted to a psychiatric hellhole where some 1,500 non-white females were held against their will. The mining compound exemplified the barbarism of the apartheid (“separateness”) system in force in 1970s-era South Africa.

Reporters documented that the people held captive at this site and others lived under abominable conditions and were exploited as slave labor by the white owners—working 12-hour days to make bags, belts, coat hangers, mats and other items that outside commercial firms would sell.

Freedom had unearthed a network of privately owned, profit-making institutions that held nearly 11,500 black inmates—and was subsidized by the apartheid government.

“Of course we make a profit, or we wouldn’t be doing it,” admitted David Tabatznik, a leading figure in Smith Mitchell and Company, which ran the camps.

Many of those in this “labor force” had simply been picked up on vagrancy charges, being guilty of “wandering at large” on the streets of major cities. To keep inmates subjugated, their jailers administered mind-numbing psychiatric drugs. Electric shocks were used without anesthetics. As Freedom noted, “This causes extreme pain. It can break bones and the violent convulsions can break a back.”

When Freedom published the results of its research, the apartheid government reacted by enacting laws that made it a crime to photograph the facilities or to report about them.

Undaunted, Freedom staff took their information to the United Nations, which commissioned the World Health Organization (WHO) to investigate. WHO confirmed what Freedom had uncovered, declaring “the chain of private institutions … is a tool for human rights oppression and racial discrimination.” The chairman of the U.N. Special Committee Against Apartheid, Leslie Harriman, noted that the investigation “reveals not merely gross discrimination against the African people … but the callousness and inhumanity of the apartheid regime which refuses to treat the African people as human beings.”

Separately, a team of four medical doctors traveled from the United States to South Africa and conducted a 17-day survey, reporting in The American Journal of Psychiatry in November 1979 that, “We found unacceptable medical practices that resulted in needless deaths of black South Africans. Medical and psychiatric care for blacks was grossly inferior to that for whites. … We believe that these findings substantiate allegations of social and political abuse of psychiatry in South Africa.”

The Spectator noted that copies of Freedom exposing the camps had been seized based on a warrant signed by apartheid advocate and government minister Connie Mulder and that “the South African Publications Control Board of Censors (run by Mulder), banned Freedom.”

“During his ten years as Minister of Information—and as Minister of the Interior from 1972—Mr. Mulder on many occasions took action to guard the Smith Mitchell mental homes from their various critics, of whom the most persistent have been the Church of Scientology,” The Spectator reported, noting that in the 1960s Mulder had served as a director of two camps. Although he resigned from those positions in 1968 when he became a cabinet minister, he held on to major shares of Smith Mitchell investments.

With the end of apartheid in 1994 came a charter for the protection of patients’ rights. And with the change in government came recognition of actions taken by Freedom and the Church to tear down the curtains that had covered up abuses.

Today, Freedom and the Church continue their efforts to improve conditions within that nation’s mental health system, and to strive for freedom and equal rights for all.