The world first heard about the seven poisoned Richardson kids on October 25, 1967, at 6:30 p.m. I was sitting at the dinner table with my family, in the Breeze-Swept Estates neighborhood of Rockledge, a small town on the Indian River Lagoon in Brevard County, Florida.

“Quiet,” my father ordered, reaching for the gold and silver Space Command remote, aiming it at our brand new rabbit-eared Zenith TV set, in full view from the living room.

It was time for CBS Evening News!

And. Walter. Cronkite. Began. To. Speak.

In those days that’s the way it was. But something far beyond the pomposity in Cronkite’s presentation shocked me that night. There had been a tragedy in a small town in Florida that very afternoon. It wasn’t the routine Vietnam protest story of that era. You know, someone throwing blood on Selective Service records, or Jim Morrison or John Lennon arrested—or banned—again.

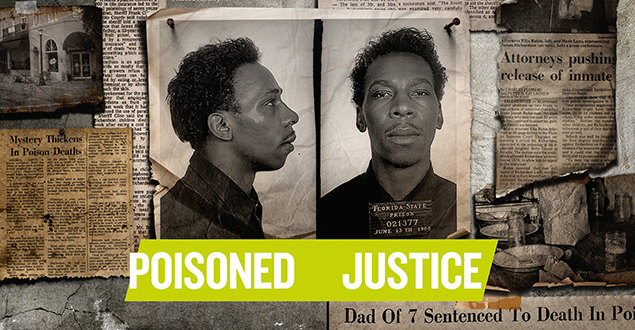

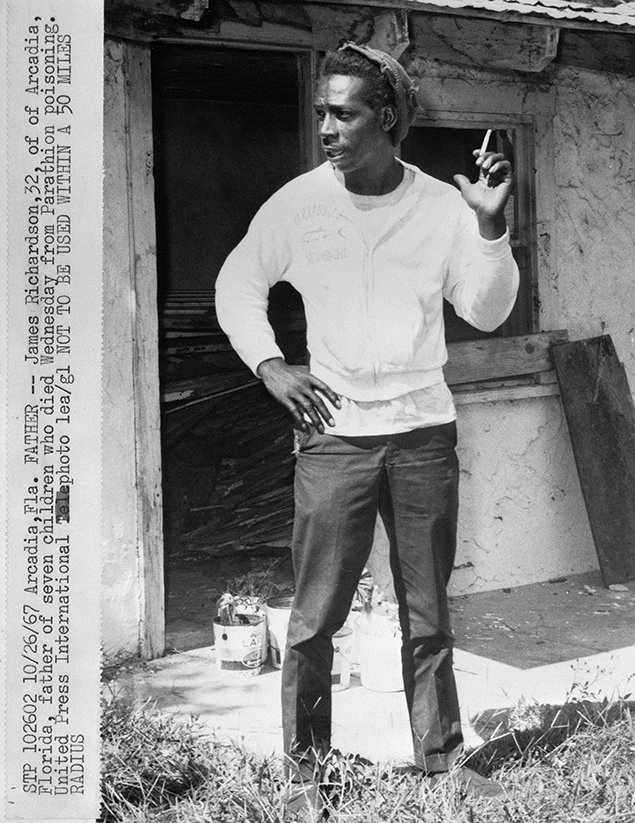

No, this was unbelievable. Seven black children poisoned in Arcadia, Florida—about 150 miles southwest of our town. Seven from the same family! Six dead, one dying. The chief suspect? Their father, an itinerant fruit picker named James Richardson. But, stay tuned. A homicide case was being built by Frank Cline, the sheriff of DeSoto County, a small Central South Florida community of rural farm fields and cattle pastures … and, as I was to find out later, renowned as a scary Florida “sundown town” of the Ku Klux Klan.

Cronkite’s deep, paced, ominous tone projected unspeakable horror as he detailed a dreadful scenario where four siblings—sisters Betty Jean, 8; Alice, 7; Suzie Mae, 6; and Doreen, 5—were stricken with violent convulsions, all at the same time, in four separate classrooms at the local, all-black Smith-Brown school, just after lunchtime.

Three preschoolers from the same family were found dead at home, said police. At the broken front door, was James Jr., 2, lifeless in the arms of a wide-eyed babysitter named Betsy Reese. At her feet was a whimpering, spastic, barely alive Diane, 3. Vanessa, 4, was convulsing in a fetal position nearby.

Autopsies said they had ingested parathion organophosphate dust—a deadly toxin citrus farmers used to kill insects.

The kids were poisoned, the sheriff kept telling the media.

By their father, he said.

For insurance.

Next day, The Miami Herald would call it “the most ghastly crime in Florida history.” In fact, Cronkite’s shocking report certified the story on the international media front pages. In the next few days, a horde of reporters converged upon Arcadia, a town of redneck chauvinists and hooded secrets absolutely unprepared to handle the judgmental onslaught of the big city media.

“Oh yeah, the media created a real rush to judgment. Those boys needed to solve the case right away and make that media attention go away before they found out what that town was all about,” says a retired state lawman very familiar with the case, who demands, nearly half a century later, anonymity.

In fact, in the pandemonium of this sensational small-town mass murder case, I found out later, veteran Judge Gordon Hays ordered an unprecedented “coroner’s inquest,” a mini-grand jury of sorts, with haste. Mixing rumor, forced testimony, and downright lies—all tinged with Southern racism—the inquest certified these children were the victims of mass homicide.

By the father.

There was no court reporter; the media was banned, except for one: the aptly named William A. “Hack” Hackney, editor of the local Arcadian news rag, whose one-sided reports are the one and only record of what transpired.

The worldwide media throng lockstepped in Hackney’s wake, repeating his exclusive fabricated screeds, piling the weight of kidnapped public opinion onto the grieving father’s shoulders.

For the most part, the dead children dropped off Cronkite’s radar a week later, after they were buried in Arcadia’s Oak Ridge Cemetery. The photos are filed in my mind’s eye: The seven little white caskets on the floor of the high school gym, and the young black girl (who would grow up to be mayor) singing “Amazing Grace.”

Over the years, boaters on the nearby Peace River have reported eerie orange orbs accompanied by a big wind often seen at dusk and dawn near an area known as Goat Hill. These are the souls of the Richardson kids, legend says, seen with mysterious regularity, to this very day.

In 1970, I read attorney Mark Lane’s book about the Richardson case, Arcadia, in which the author concluded Richardson had been railroaded by white lawmen, calling for a new trial. Lane, who later defended Richardson, was exactly right. But a combination of shrill writing, non-objective bias and his highly controversial self-promoting nature turned off the media. News columnist George Will called Lane, “the affliction of the afflicted.”

Richardson was tried for the murder of one child—stepdaughter Betty Jean—and was convicted in a real-life version of the stereotypical Southern kangaroo court and sentenced to die. If that trial hadn’t worked, the sheriff vowed, “we’ll keep trying him for each child, one after the other, until he’s found guilty!”

“We’ll keep trying him for each child, one after the other, until he’s found guilty!”

From the very first day, Richardson was the only suspect.

In fact, he and his wife, Annie Mae, were 14 miles away picking fruit when the children ate both breakfast and lunch. Richardson was no angel. He had a lengthy juvenile record, even spending time at Marianna Correctional School for Boys. In June of 1963, Richardson’s son (with previous wife Margie Westbrook), Sampson, arrived DOA at Duval Medical Center in Jacksonville. Local police noted the father had brought the baby in earlier that day for extreme vomiting; the case was later closed on July 2, 1963, as a “natural death.” No autopsy was performed.

Years later, Sheriff Cline would report that Sampson had died after eating uncooked beans and that the mother, Margie, left for Detroit with their other three children because “she felt Richardson was instrumental in the child’s death and was afraid the others might eat some beans and die.”

Annie Mae Richardson, prior to leaving with her husband for the grove, had made chicken sandwiches for her children’s breakfast and a small pot of grits cooked into a stew of rice and beans for their lunch.

The Richardsons were a very dysfunctional family. Migrant farmworkers, constantly moving, both wife and husband habitually walking away to adulterous liaisons, then returning. Seven months before the children died, Annie Mae obtained a warrant for the arrest of her absent husband for nonsupport. Four days before the children died, a warrant was issued for Richardson for desertion and nonsupport by ex-wife Margie Westbrook.

Incredibly, no one—except folks on the street—bothered to shine a spotlight on 32-year-old babysitter “Big Mama” Reese, the next-door neighbor who served the poisoned food. The sheriff and state attorney both knew that Reese’s first husband died mysteriously after eating a stew she cooked, and that she was still on parole for shooting her second husband dead.

Investigators found traces of the poison everywhere, sprinkled in the sugar bowl and talcum powder, in a bag of laundry powder purchased the night before, in the sack of self-rising flour, in the cold jar of used lard, in the bag of Martha White corn meal, inside a locked refrigerator, on items of clothing worn by both children and parents, traces of the killer dust everywhere—enough, scientists later testified, to kill everyone in town.

Suspect Richardson explained the business card found in his pocket, that morning, which listed the children’s names and ages (including three kids who did not even live there) scrawled on the blank side; Richardson told Cline he had spoken to a door-to-door insurance man who had stopped by, unannounced, the night before.

The card read, “Gerald Purvis, Union National Life Insurance Co.”

To State Attorney Frank Schaub and Sheriff Cline, however, it screamed “motive.” They hurried to talk with Purvis, who denied, repeatedly, that Richardson had purchased coverage. Nevertheless, Schaub told the coroner’s panel that Richardson killed the children to collect from an insurance policy he had purchased on them only the night before.

That was a lie.

Schaub’s allegations carried great weight in that part of Florida. Only six months before, he gained national prominence by out-lawyering celebrated defense attorney F. Lee Bailey, proving Bailey client, Carl Coppolino, poison-murdered his wife—the first loss in 19 straight homicide cases for Bailey. A seasoned lawman, whose district once covered Key West north to Tampa, Schaub was a legend, the dean of Florida’s prosecutors.

Yes, Frank Schaub knew a poisoner when he saw one.

(During an interview I conducted with Schaub years later, the man became suddenly enraged at my questions regarding the Richardson case. He rose from his chair and lunged at me over his desk, with a fist held high that he slammed down right in front of me, sending papers and pens all over the floor. Then he had his goons escort me from his office.)

A NEW LOOK

After graduation from the University of Florida, and a short stint as a U.S. Army draftee, I returned home to Rockledge in 1973 for a sports writer job at the (Cocoa) Today newspaper; two years later, I was hired to join the news-features staff at the St. Petersburg Times. The Times editor was Eugene Patterson, a noted civil rights pundit who had won a 1967 Pulitzer Prize for his moving editorial in the Atlanta Constitution after a Birmingham, Alabama, church bombing that killed four young black girls.

I asked Patterson if we could revisit the Richardson case. My instincts regarding Richardson’s innocence, then unsupported by hard evidence, were not enough, however; Patterson wasn’t interested in a new look at “Florida’s most ghastly crime.”

A decade later, in 1985, I accepted a job offer from Chairman James Billie of the Seminole Tribe of Florida, who I knew as a fellow musician at the annual Florida Folk Festival. He was a charismatic leader and Vietnam battlefield veteran who employed military terms in my recruitment around a Big Cypress campfire: “I need a Pen,” he told me. “I’ve got a Map man. I got a Sniper. I need a Pen.”

My direct supervisor became Betty Mae Jumper, the legendary editor of the Seminole Tribune, the Tribe’s official newspaper. Betty Mae was the first Seminole Indian to graduate from high school. She based her decisions totally on her intuition and unwavering belief in what is right and what is wrong.

One day, in spring 1988, while driving over the Skyway Bridge, broadcaster Paul Harvey came on my car radio speaking about an old demented woman slowly dying in a Wauchula, Florida, nursing home who kept telling her nurses: “I killed the children. I killed the children.”

And “the rest of the story?” The old woman was none other than Betsy Reese, the Richardsons’ babysitter. Nurse Belinda Frazier later signed an affidavit that Reese confessed to her more than 100 times between 1985 and 1987.

I drove directly to Tribal headquarters and walked in on Betty Mae; she was writing (with pencil on loose-leaf paper). “There’s a story I think we should do, Betty,” I said, when she looked up.

“Did he do it?” she interrupted.

I told her my instincts said no: “I want to go visit the man in prison, talk to him face to face.”

“Go get him out,” she concluded, matter-of-factly, authorizing what would be nearly a year’s worth of research. “If he didn’t do it, then go get him out.”

I enlisted the help of Charles Flowers, a noted South Florida investigative reporter, who joined me to meet Richardson at Tomoka Correctional Institution near Daytona Beach. Daytona Beach civil rights activist/attorney John Robinson also met us there. “I’m his whole hope in the whole world,” Robinson had told the Orlando Sentinel. “He loves me like a brother, and I love him like a brother.

“If there was ever a possibility that he committed that type of crime, I wouldn’t even spit on him. If I thought he was guilty of committing an atrocious crime like that, I’d pull the switch on him myself.”

The case began to unravel as soon as we walked through the foreboding barbed wire surrounding the prison. Warden Leonard Dugger was intense: “Every person in prison says he’s innocent. The difference is, Mr. Richardson really IS innocent.”

There was no doubt in the warden’s mind: “Men who come to prison for killing children do really hard time. They get beat up. They get tortured and killed. Nobody treats them decently. Guards, fellow inmates, staff. But this man has a totally clean record, not a single black mark in 21 years. Everyone knows he is innocent.”

Richardson greeted us warmly. His was the air of a preacher, close-cropped graying hair and large thick eyeglasses. We sat down and talked. I remember staring hard at his face, trying to find something, anything, that would make me see a child murderer. I noticed everyone who walked by—guards, staff, other inmates—greeted him as MISTER Richardson.

He remembered his last day of freedom, the day the children died. He and Annie Mae sat beneath a tree in an orange grove miles outside of town, eating sandwiches from the same batch left for the children, and waiting for a light rain to subside. “I was telling her that I was gonna make love with her when I got home. And she was telling me, ‘I bet you ain’t as good as I am.’

“We had adorable times out there,” he said, describing the grove as “like a lover land, you know. It was the most pleasant and happiest time I had in my life.”

EARLY SIGNS

“Lover land” disappeared forever on Wednesday, October 25, 1967.

A terrible commotion commenced inside the old school building a few blocks from the Richardsons’ home. Four sisters collapsed at their desks, floods of mucous pouring out of every bodily orifice. “They were all dying right before our eyes,” said schoolteacher Ruby Faison, whose thoughts went to events exactly one week before, when dozens of Tijuana residents, most of them schoolkids, died or were hospitalized from parathion-laced bakery bread.

Three more kids had collapsed at home. Police quickly arrived. A chemical smell was in the air, but no sign of any poison, despite five searches of the apartment and a shed outside. The sheriff, born and raised in Arcadia, figured the smell as parathion, a compound created during World War II as a gas weapon by the Nazis, now widely used on Florida citrus.

There is no evidence Reese’s adjoining apartment was searched.

Reese told police she served the children breakfast sandwiches and, later, a lunch of beans, rice and grits—all pre-prepared and stored in a locked refrigerator. A chunk of headcheese, for the babysitter to fry up with flour, would supplement the lunch. The children ate, walked to school, returned for lunch and, without incident, walked back to school.

“Every person in prison says he’s innocent. The difference is, Mr. Richardson really IS innocent.”

When the Richardsons arrived at the emergency room, babysitter Reese was standing outside. “Go inside,” she said. “They tell you inside.”

An entourage, led by Sheriff Cline, stopped Richardson, completely ignoring his questions: “Why are we here? Where are my kids?”

Cline, Richardson says, only “asked me did I have insurance on my kids. I said no. I didn’t pay no insurance.”

An hour later, Richardson says, a priest arrived: “He said, ‘We need to pray.’ … I said, ‘Pray for what?’ He said, ‘Let’s drop our heads and pray.’ I said, ‘What we gonna pray about?’”

Richardson recalls an unidentified man finally told him: “He said, ‘We have to give you all bad news. All your children is dead.’ So I told him he was a damn liar. So, then I was praying (and) before I could look up, my wife had done passed out.”

Later, when time came to identify the children, Annie Mae fainted again. Said Richardson: “I looked up and seen one of the kids lying there. Just lying there. There were two in the hallway … One sheet come back on one. The cover come back and she say, ‘I’m all right. I want to go home with my mother and father.’ And she lay back down and died.

“Then I went in the room and all the rest of them were lying there under white sheets.” Richardson was in “deep shock” he told us. His stoic behavior was used by prosecutors to portray him as a cold-blooded killer.

Nearly 21 years after that fateful day, Richardson shuddered as he recalled how the babysitter’s children used to eat every morning with his children. “In the morning, my wife fixed food all the time that she would leave for the babysitter to fix up and warm and feed to all the children.

“I said: ‘On that day, however, her children weren’t there …’

“That frightened me … That day. Why? Why didn’t the babysitter’s children eat with my children on that particular day? I am worried about that. What is the motive for it? I could never understand.”

The coroner determined the children were homicide victims. But who did it?

In fact, early that morning, Reese had summoned her sister to drive nine children, including her own daughter and five grandchildren, to Sarasota. Only the Richardson kids ate the poisoned food.

Only one child survived past nightfall. Three-year-old Diane died the next morning just as town drunk Charlie Smith, accompanied by Reese, “found” a bag of parathion, in the shed police had searched the day before. The bag was taken for evidence; oddly, it was damp while the shed was bone dry.

DEATH ROW

Jail inmates told Richardson that Reese was mad at him for giving her husband a ride to Jacksonville, where he stayed, refusing to return. “He was the smartest one of all this bunch of characters,” said Ellis Rubin at that time. Rubin, a famed, showboating Miami lawyer, died in 2006. “He probably saved his life by escaping Reese!”

At a press conference, Cline announced that Richardson had five other children who had died mysteriously in Jacksonville; he said the motive for this crime was collecting $14,000 in insurance money—entirely unproven allegations—and Cline knew it. Irritated, Sheriff Dale Carson of Duval County, who fielded dozens of media inquiries, offered to write an official letter clearing Richardson of any Jacksonville crimes.

But who would he write it to? Richardson had yet to engage an attorney. Sadly, the media was no help, hyped up as it was by Cline and Schaub’s manipulations.

Prodded by Cline’s findings of past dead Richardson children, the coroner’s “inquest” officially substantiated the evidence and determined the children were homicide victims.

But who did it?

Never one for impartiality, Judge Gordon Hays, a local jurist in Arcadia for more than 31 years and one of the most influential and powerful men in DeSoto County, took care of that, announcing that results of lie detector tests showed Richardson had “knowledge” of the poisoning.

In 1967 DeSoto County, that meant he was guilty as hell.

“We will meet today to instruct Sheriff Cline to file murder charges against Richardson,” declared Hays.

Case closed. The verdict was written in stone before any trial even began.

Attorney John Robinson agreed to represent the fruit picker pro bono. The white, 30-year-old Robinson was a civil lawyer who had never defended anyone at a criminal trial.

From their first conversation, Robinson said Richardson complained about his treatment in the Arcadia jail: “He told me how Sheriff Cline would constantly push him around and call him a nigger.” Robinson removed a microphone Cline placed in Richardson’s cell.

On December 6, 1967, a county grand jury returned an indictment of first degree murder against Richardson. Bail was set at only $7,500.

Immediately, new evidence emerged from jail inmates. Both James “Spot” Weaver and James Cunningham swore Richardson had confessed. Cellmate Earnell Washington said Richardson confided that “he wanted to get rid of his wife and children because he wanted the money and to go back with his other women.” Washington said Richardson told him “during the night with the wife not home, he put poison in the stuff they use and the sweet powder.” And the next morning, Richardson “put [poison] in the grits while the wife was dressing the children.”

All three men, including Washington, who was in jail for assault with intent to commit murder, were immediately released after depositions and agreements to testify.

Washington, however, was stabbed to death in a local pool hall.

After deliberating 84 minutes, an all-white jury returned with a guilty verdict.

Richardson’s 12th Judicial Circuit (Case 3302D) murder trial began May 27, 1968, at the Lee County Courthouse in Fort Myers, with John Justice presiding. Remarkably, Justice allowed the late Washington’s pretrial depositions to be read by the voices of Fort Myers News Press reporter Thelma Ted Bryant, Associated Press reporter Richard Oppel, a real estate broker, a local salesman, and Assistant State Attorney John Treadwell.

State Attorney Schaub closed his part of the trial, never calling Smith, who found the parathion, nor Reese, who fed the children, nor Purvis, the insurance man, to the stand. In an Orlando Sentinel article, Schaub said Reese wasn’t called because “we didn’t feel she was competent. She’s never been mentally alert.”

Amazingly, the testimony of Purvis and Smith was of “no consequence,” said Schaub. Not knowing what the prosecution knew about those witnesses, Robinson didn’t call them either.

With Robinson clearly outgunned, nothing prevented Schaub from arguing as if all relevant testimony had been given. On May 31, 1968, after deliberating 84 minutes, an all-white jury returned with a guilty verdict, recommending James Richardson be put to death.

Richardson was immediately sent to Florida State Prison’s Death Row. The appeal of his conviction and death sentence were both denied in 1971. The next year, the U.S. Supreme Court landmark Furman vs. Georgia case declared the death penalty unconstitutional, and Richardson, who had undergone several fake execution exercises, had his sentence commuted to life.

LIES AND MORE LIES

At the Seminole Tribune, it became obvious we were unearthing information that was not new … yet it was! Facts known only to lawmen who sent Richardson to Florida’s “Old Sparky” electric chair. The jury, the defense, the media had never heard stories we were detailing in the bimonthly Tribune and, later, in The Miami Herald, which published our daily breaking stories, and a future Sunday magazine overview of the case.

We tracked down former inmate Spot Weaver, who had said that Richardson admitted he had killed the children “to get out from under it all,” and “to get back at his wife for cheating” (with—of all people—babysitter Reese).

“I lied,” Weaver said, matter-of-factly, when we found him in Bartow. “I was scared. I was afraid of the whole thing. In those days, it was kind of rough for a colored man”—especially in 1960s-era Arcadia, where the Ku Klux Klan marched in the annual Christmas parade.

Weaver said he had been paid a visit in jail by Deputy John “Bad Boy” Boone, who was called in by Cline to “assist” with the investigation.

Boone beat prisoners to get them to testify against Richardson, according to Weaver.

We found the tall broad-shouldered, menacing “Bad Boy” Boone, sitting out his retirement on the steps of Mrs. Boom’s (sic) Boarding House in Immokalee.

“Did you threaten to beat Spot Weaver and James Cunningham (by now deceased),” we asked, directly.

“Sure, it could have happened,” Bad Boy admitted, without hesitation, and in a very soft voice. “It was a different time back then. If the sheriff said to do something, you did it. Those were frontier times. It was my job.

“Anyway, Richardson WAS guilty,” Boone said, in his defense, his whispery tone rising. “He had to be.”

The sheriff told him so.

We finally tracked down insurance man Purvis, suffering from grave COPD, lying in a full body plexiglass iron lung in his living room; he told us vigorously that, in fact, Richardson did NOT purchase insurance, “nor did he THINK he had purchased it. He had no money until his payday at the end of the week.”

The coroner’s inquest news story written by juror/Arcadian editor “Hack” Hackney portrayed Purvis as admitting that he MIGHT have left the impression on Richardson that his coverage WAS in effect. Hackney’s description of the conversation between fruit picker and insurance salesman was a repartee that Purvis called “an incredible fabrication.”

Hackney also published a strange “historical” factoid that came from no other known source: “That evening when (Purvis) called to report the day’s business to his superior, he noted that he had sold a policy to a man who seemed ‘more anxious than usual’ to have the insurance written.”

“He has taken my words out of context there. That is not what I said,” said Purvis, adamantly.

BURIED EVIDENCE

An Arcadia resident named Remus Griffin called us with a crazy story. His girlfriend, a secretary for State Attorney Schaub’s ex-assistant Treadwell, had found a sealed legal box of documents hidden in Treadwell’s desk—paperwork from the 1967-68 Richardson case. Crucial information, she said, exculpatory evidence that could have exonerated James Richardson 21 years before.

In 1979, Griffin broke in and stole the box. “That file was the property of the people of the state of Florida,” Griffin would later declare. “At worst, what I did is break into his office and get something that belonged to the state of Florida.”

Griffin admitted, “It scared the shit out of me,” causing him to store the box in a friend’s trailer near the remote Devil’s Garden area of the spooky Big Cypress Swamp. But now, 10 years later, he wanted us to have the box. He told me to call the G. Pierce Wood State (Mental) Hospital, after midnight, and “ask for ‘the Contessa.’”

So, I did that. Somewhere from deep in the darkness of the institution where the state’s most mentally deranged criminals lived, the Contessa came to the phone. No small talk. Just quick directions and an order to be there the next day by 6 p.m. I called Seminole Chief James Billie, who lived near there, and told him about the box. “That’s a dangerous area that late in the day,” he said. “I better go with you.”

As we rolled toward our destination, a pistol appeared on the seat between us. “When we get out of the car, if you hear shots, just drop to the ground and start rolling,” he ordered, “and let me take care of it.”

Instead of a confrontation, however, it was Old Home Week when we pulled in the driveway of an old trailer with junk everywhere. An older woman in too-long pigtails ran out to give the Chief a big hug.

It turns out the nervous Griffin had retrieved the box that very morning and, without telling us, brought it to John Robinson. The box made Robinson nervous, as well, and he carried it to Daytona Beach, where he gave it to lawyer and conspiracy writer Mark Lane in his condo.

Lane had contacted Robinson after the 1988 Paul Harvey report, offering his legal services. “He had more experience than I do with criminal investigation documents,” said Robinson. “He had written a book exposing the system that railroaded Richardson. He will know what to do.”

PROVING INNOCENCE

Lane had the contents of Treadwell’s box spread out on the kitchen counter of his penthouse beachside condo when the doorbell rang. Lane was surprised when Flowers and I appeared at his door. But he let us in.

“What are you doing?” he roared when I took out my camera and began photographing the pages. He brushed by me and quickly gathered up the documents, placing them back in the old box.

“This is evidence. This has to go to the courts,” he stammered, quickly ushering us back out the door. “You’ll see it soon enough.”

We were eventually shown the documents by attorney Ellis Rubin, who took over the reins as Richardson’s principal attorney.

Evidence in the box included transcripts from jailhouse snitch interviews, containing conflicting accounts of Richardson’s “confessions.” The entire insurance “motive” was discounted in depositions with both Purvis and Richardson. There were also prosecutor’s notes about Reese’s violent criminal background and documents suggesting revenge motives attributed to Reese.

Finally, on Sunday, December 11, 1988, under the careful editing of The Miami Herald Tropic Editor Gene Weingarten, our story “Poisoned Justice” appeared. The unique joint effort of the Herald and Seminole Tribune was later honored by the Robert F. Kennedy Foundation.

Richardson, through Rubin, immediately filed a request for a new trial with the Florida Supreme Court.

The story that the father was likely innocent of the most heinous child murder in history, was reported worldwide. We left to meet with Governor Bob Martinez, carrying a graphic chart I created from hidden documents that gave rise to the possibility Reese simply grabbed the wrong bag when she needed flour to fry up the hogshead cheese that fateful day.

An accident, maybe? Reasonable doubt, at the least.

We had no appointment. Martinez would not see us, said his secretary. However, I saw Martinez through his open office door. I rushed in, introduced myself and handed the chart to the governor, who politely ignored my intrusion and stared at the chart intently. When capitol police stormed in, he waved them off.

26 years after his freedom and declaration of innocence, he received a [first] compensation check.

Eventually, capitol beat reporters gathered to investigate the commotion with the governor. I gave Martinez my card and started to walk out of the room. Immediately, a phalanx of reporters filed in. I saw St. Petersburg Times reporter Lucy Morgan grab the chart; when she began perusing it, I took it from her hands, saying, “This is my property, thank you.” I pushed through the group and handed it back to the governor, who smiled and placed it behind his desk … out of Morgan’s reach.

“You’ll find out soon enough,” Martinez told the group. “There’s no story here right now.”

On February 1, 1989, Martinez ordered a special investigation into Richardson’s murder conviction, appointing Miami-Dade State Attorney (soon to be U.S. Attorney General) Janet Reno as special prosecutor and issuing an executive order directing the Florida Department of Law Enforcement to investigate any alleged violations of criminal law by the state of Florida or misconduct on the part of public officials.

The Florida Supreme Court chose retired Circuit Judge Clifton Kelly, 71, of Highlands County, to hear Richardson’s request for a new trial. Kelly, a respected and dignified jurist familiar with the ways of life in rural Central Florida, was the perfect choice.

The State vigorously opposed any new trial. Incredibly, Schaub, himself, came out of retirement to declare that “It’s one of the strongest cases I have ever presented to a jury.”

On May 2, 1989, Judge Kelly conducted an evidentiary hearing and, after hearing more than eight hours of arguments, took 35 minutes to grant Richardson’s motion to vacate his conviction and sentence. All charges against Richardson were nolle prossed (terminated). Kelly ordered a new trial and Richardson’s immediate release.

In a memorable oration, Judge Kelly stated: “The enormity of the crime is matched only by the enormity of the injustice [done] to this man.”

Richardson filed suit against DeSoto County for wrongful conviction and eventually settled for $150,000, most of which went for legal expenses incurred since 1968.

Janet Reno’s “Nolle Prosse Memorandum of May 5, 1989” laid it all bare. The trial was “nothing more than a farce, with the State presenting arguments, theories and testimony, which it knew was directly contradicted by evidence in its (hidden) file and which was not known to the defense attorney or the Court. Had someone not broken into the office of the former assistant state attorney, stolen the files and forwarded them to the governor’s office, Mr. Richardson might still be sitting in prison and the egregious nature of the State’s (and sheriff’s) actions in this case might never have been uncovered.

“Not only couldn’t the state prove James Richardson was guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, but James Richardson was probably wrongfully accused.”

A few years later, Schaub was suspended for 30 days for prosecutorial misconduct for his transgressions during an unrelated case. Among the charges were “knowingly making a false statement of material fact or law to a tribunal” and “knowingly failing to disclose a material fact to the defense.”

Sound familiar?

Even after Schaub died in 1995, the DeSoto County State Attorney’s office watchdogged Richardson’s compensation quest, proactively lobbying for dismissal. “They were at almost every meeting. All they would do is sit there and go ‘I object, I object, I object’ to everything James’ attorneys brought up,” remembers Tim Edmonds of Melbourne, whose family had become special friends and caretakers for Richardson since his release from prison.

Because of the way Richardson’s conviction was overturned—special prosecutor’s review rather than court-overturned—his $1.2 million compensation was constantly denied in numerous court hearings and legislative actions over more than 20 years.

Make no mistake about it, the ugly smear of Southern racism once again settled firmly over James Richardson, in the guise of the DeSoto objectors still defending their bruised heritage of justice.

Finally, in June 2014, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed HB 227. The bill provides compensation to a wrongfully incarcerated person convicted and sentenced prior to December 31, 1979, whose case was reversed by a special prosecutor’s review. Richardson may be the only individual eligible under this restricted law.

Forty-seven years after James Richardson’s wrongful conviction and death sentence, and 26 years after his freedom and declaration of innocence, he received a compensation check. He will receive ten checks for $112,000 each year through 2025 ($25,000 from each check goes to the attorneys and lobbyist who navigated Richardson’s case through decades of legal hoops).

A recent documentary film about Richardson has been touring national film festivals. Time Simply Passes, produced by Ty Flowers, son of investigative journalist Charles Flowers, documents Richardson’s life and times, concluding with the vote to grant him compensation. Years earlier, Richardson signed his rights to a major motion picture company, but the movie was never made.

James Richardson, 81, lives today at an undisclosed location in Wichita, Kansas, with his wife, Teresa. He worries that if people find out he has money, someone will rob him. Open-heart surgery in 1987 (in prison; he could never have afforded it as a free man) saved his life. His nemesis, former Sheriff Cline, lost two elections in the 1980s and retired to Port Charlotte, where he died in October 2013.

A few weeks before Christmas 2016, Richardson was hospitalized.

“I think it was just something he left out of the refrigerator too long,” said longtime friend Tim Edmonds. “Or maybe something he ate after the due date. He was pretty sick for a while there with food poisoning.”