And it’s not just bots or clickbait. The survey, released April 24, lands amid a surge of AI-generated news anchors broadcasting deepfake headlines in local dialects; social media clips misrepresenting wars by slapping Gaza tags on Syrian footage; and websites dressed up to resemble hometown papers, complete with weather widgets and obituaries—only to quietly push propaganda. As misinformation grows more sophisticated, the institutions meant to keep it in check appear, to many, increasingly unreliable.

Titled “Free Expression Seen as Important Globally, but Not Everyone Thinks Their Country Has Press, Speech and Internet Freedoms,” the survey offers further proof that fake news isn’t just a nuisance—it’s a crisis.

Globally, only 28 percent of respondents believe the media in their country is “completely free” to report the news.

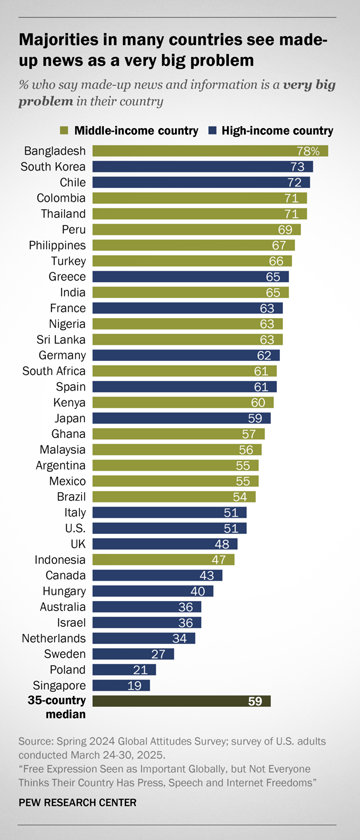

In the US, more than half of adults (51 percent) now view made-up news as a “very big problem.”

In Canada, 43 percent of the population worries about fake news. And across much of Europe, roughly half or more of the population shares the same anxiety, with Greece (65 percent) topping the list, followed by France (63 percent), Germany (62 percent), Spain (61 percent), Italy (51 percent) and UK (48 percent).

It’s a troubling contradiction: As public concern over false and misleading information rises, trust in the very outlets expected to confront it—legacy newspapers, broadcasters, even international wire services—continues to fall. Globally, only 28 percent of respondents believe the media in their country is “completely free” to report the news, with an additional 38 percent saying the media are “somewhat free” to do so.

The Pew report also notes that in Canada, 77 percent of adults say freedom of the press is very important—10 points higher than in the US, where such liberties are enshrined in the First Amendment and long touted as a democratic hallmark. The contrast is striking: Although American ideals once shaped the global narrative around press freedom, today it is Canadians who express stronger support for that same principle.

This disconnect between democratic ideals and lived reality appears again in attitudes toward free speech. Across the globe, a median of 59 percent say it is very important to have freedom of speech—yet only 31 percent believe it is fully protected in their own country. Pew found this so-called “freedom gap” in 31 of the 35 countries surveyed, revealing a widespread sense that core liberties are more valued in theory than secured in practice.

Some of the report’s key findings on the US media echo a 2019 Pew Research Center study, which found that Americans largely harbored such deep skepticism toward news outlets that they ranked fake news and misinformation as greater threats than terrorism, racism or climate change.

The same pattern emerges across Europe: Citizens value press and speech freedoms, but feel they are slipping away, according to the latest Pew survey. Germany, Spain and Italy all show significant gaps between support for these rights and belief in their current vitality.

These gaps are more than statistical curiosities—they correlate directly with democratic disillusionment. In many of the surveyed nations, those most concerned about misinformation are also the most dissatisfied with how democracy is functioning.

The fear isn’t just about bad information—it’s about the institutions that are supposed to filter and fight it. It’s the sense you get when a false story spreads faster than its correction, or when a politician’s lie trends for days while the fact-check quietly expires in a corner of the internet.

In much of the Asia-Pacific region, concern over fake news also runs high, with over 70 percent in Bangladesh, South Korea and Thailand calling it a major problem.

The latest Pew report makes one thing clear: Fake news isn’t merely a nuisance or fringe phenomenon. It’s a symptom of deeper democratic malaise that transcends national borders and is expressed in a crumbling confidence in institutions tasked with telling the truth.

Across the US, Canada and Europe, citizens are not just asking, “What is true?” They’re asking, “Who can we trust?” The answer, as ever, may lie not in a single institution but in a culture of vigilance and accountability—in local libraries hosting media literacy workshops, in high school civics classes updating their curricula and in readers who pause before they share. Trust, after all, is not a given. And rebuilding it begins with learning to tell the difference between fact and fabrication.