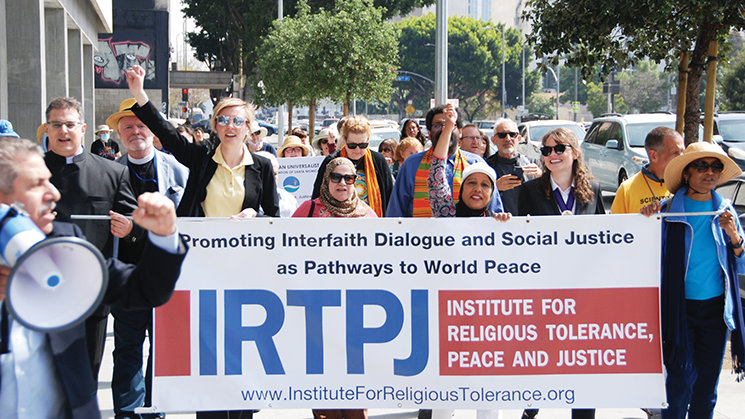

It was a balmy Sunday in Southern California when Angelenos joined thousands around the world in observance. This year, Los Angeles marked the day with the 10th annual Interfaith Solidarity March, organized by the Institute for Religious Tolerance, Peace and Justice (IRTPJ) and emceed by a minister of the Church of Scientology. Lasting five hours, the walk carried the theme: “Faiths in Unity: Reclaiming Our Humanity.”

The significance of the march resonates beyond symbolism. In a world roiled by brutal wars, ethnic cleansing, terrorism and surging hate crimes at home, diverse faith traditions—united and mobilized in a common call for peace—comprise one of the few remaining civic forces that can cross social, political and spiritual divides.

“I see religion as being the last bastion of humanity—the last sites of hope, human dignity and respect.”

The afternoon began at St. Basil Catholic Church, a Brutalist landmark on Wilshire Boulevard. Here, Dr. Arik Greenberg, Clinical Assistant Professor in Interreligious Dialogue at Loyola Marymount University and founding president of IRTPJ, addressed the marchers.

“Our nation and our world have seemingly lost or forgotten our shared humanity on many levels,” Dr. Greenberg said. “In our nation, we’re seeing increased hatred, polarization, entrenchment and tribalism.”

He warned of “increases in religious bigotry and intolerance … an increase in hate crimes, mistreatment of those at the bottom of society and even political violence,” adding that “overseas, we are seeing brutal, endless wars and ethnic cleansings, and even genocides.”

Greenberg invoked the words of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, a prominent Jewish theologian and activist who, when asked if he had time to pray during the 1965 Selma-Montgomery march with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., famously replied: “I prayed with my feet.”

“Maybe that can inspire us in our work today,” Dr. Greenberg told the crowd. “To envision this [march] as an act of prayer, of devotion—to whatever God we pray to, if any at all. That we are sending out positive vibes of love and friendship to all the Earth and all the cosmos, in a way that every major world religious leader has preached for thousands of years.”

The theme of religion’s role in repairing a fractured world was carried forward by Dr. Brad Stone, professor and graduate director of philosophy at Loyola Marymount University. He has attended every IRTPJ march since 2016, when the event began in support of Los Angeles’ Muslim community after a wave of Islamophobic incidents.

“I see religion as being the last bastion of humanity—the last sites of hope, human dignity and respect,” Stone told Freedom. “The Enlightenment, which was supposed to be the Great Secularization, has failed us. The 20th century actually is a history of the state failing to take care of people—the force of law doesn’t hold, and so we’re back to the soul and the spirit.”

In a world of crumbling secular institutions, interfaith dialogue has always played a vital role in promoting tolerance and peace. “If you don’t get to understand each other, then we can get to a point where … we hate each other,” Rabbi Aryeh Cohen, a professor of rabbinic literature at American Jewish University told Freedom. “There’s a direct correlation between knowing each other’s beliefs and narratives and being able to get along, especially in this country, which is made up of lots of different groups.”

Accompanied by half a dozen Los Angeles Police Department officers trained in community policing, the marchers walked about a mile from St. Basil to the Islamic Center of Southern California (ICSC) on Vermont Avenue. Along the way, they stopped at Robert F. Kennedy Inspiration Park, the site of the former Ambassador Hotel where Senator Kennedy was assassinated in 1968.

There, James Witker, a lay leader at the Unitarian Universalist Community Church of Santa Monica, spoke about Kennedy’s civil rights legacy.

“The first principle of Unitarian Universalism is the inherent worth and dignity of every human being, which is a humanistic idea that I think is expressed in some way by diverse faith traditions in modern times,” Witker said. “I think of this principle often—too often—when I hear slurs and attacks on people because of their identities. We have to keep saying, in this interfaith community, that no one is evil or violent or less than fully human because of their religion, because of their race or ethnicity, because of their sexuality, because of their gender.”

Witker then read from Kennedy’s 1968 speech “On the Mindless Menace of Violence,” delivered in Cleveland the day after Dr. King’s assassination: “Whenever any American’s life is taken by another American unnecessarily … whenever we tear at the fabric of life which another man has painfully and clumsily woven for himself and his children, the whole nation is degraded.”

“Peace is not only a dream, but a mirror reflecting the potential of our reality.”

Then, upon arriving at the ICSC, a panel of speakers addressed the interfaith crowd.

“What’s in my heart at the moment is that perhaps we never needed peace more than we do now in a country that is so polarized and so divided,” said Farrah Fazal, a Los Angeles–based Emmy Award–winning journalist. “Peace feels elusive and possible—both of those things can live in the same world,” Fazal said. “It means that we have to fight for it.”

Fazal explained her responsibility in concrete terms: “I have numbers on my phone that I can call. I have friends I can talk to. I can come to places like this and form community with people like you, so we together are going to do that work.”

Joining the discussion remotely from Berlin was Amir Sommer, an Israeli-Palestinian peace activist, author and poet. As the child of a Palestinian Muslim father and an Israeli Jewish mother, he described his heritage as “a cultural taboo.”

“For me, peace was always something holy—religious, spiritual and mandatory, such as oxygen, water, bread,” Sommer said. But today, he lamented, peace has been reduced to what he called “filthy peace—dirty peace—related to economics and military [deals] rather than something spiritual.” The audience applauded when he declared: “Peace is not only a dream, but a mirror reflecting the potential of our reality.”

Rabbi Cohen, who also spoke on the panel, confessed to his anguish over both foreign wars and domestic conflicts. “Many times during the day—most of the day—I am on the verge of tears about what’s going on in Israel and Palestine, what’s going on here, right outside our door,” he said. “Talking about peace is a stretch. What I wish for is the cessation of violence. And the only way to stop violence is [by] recognizing that every time you [put] violence—defensive as well as offensive—into the world it just creates more violence.”

By the time the marchers concluded, they had carried not only banners and chants but also a wide range of griefs and visions. For Dr. Greenberg and IRTPJ, the march was a living prayer. For Stone, it was a reminder that only the spiritual could restore dignity where secular institutions have failed. For Cohen, it was a cry of pain against cycles of violence. For Fazal, it was a neighborhood test of solidarity. And for Sommer, it was the insistence that peace remain sacred, not transactional.

But what united them all was a conviction that, however fragile, interfaith solidarity still matters—that, in walking side by side, even briefly, Angelenos could reclaim at least a fragment of shared humanity.

The march ended where it began—not physically, but spiritually. At St. Basil, Dr. Greenberg had invoked Heschel’s “prayer with feet.” By day’s end, that metaphor had become reality. The walkers dispersed into Los Angeles, carrying with them Kennedy’s plea to “bind up the wounds among us,” Cohen’s insistence that cycles of violence can be broken and Fazal’s reminder that peace must be fought for in the most ordinary corners of daily life.

If 44 years of International Days of Peace can teach us anything, it is that peace is not a single achievement but a continual walk—one that demands to be made again tomorrow—and the next day, and the next.

As Scientology Founder L. Ron Hubbard said: “On the day when we can fully trust each other, there will be peace on Earth.”