MEDIA. AND. ETHICS.

The combination can be perplexing. Ethics—in the lexicon of rank-and-file journalists—typically means that reporters shouldn’t take gifts, gratuities or favors from sources. Call it what you will, but many within the journalism industry consider it “bribery.”

Some years ago, when I worked for The Tampa Tribune, I was at a Chamber of Commerce breakfast. Ahead of me in line was a reporter from the rival St. Petersburg Times who loudly announced that she wouldn’t accept a free cup of coffee because it was against her employer’s ethics rules. I quipped—loudly as I recall—to those around us: “Aha! Now we know that the journalistic soul of a reporter can’t be purchased for the price of a cup of java.”

Were ethics served by the reporter refusing a free cup of coffee? I doubt it. But while journalists have long stroked their chins and engaged in lengthy discourse on whether accepting a free coffee—or a meal or tickets to a ballgame—is unethical, top executives of media enterprises—corporate owners, publishers and news executives routinely engaged in much more obvious ethical violations.

Media bosses manipulate news—fabricate, distort or bury information—to benefit themselves or their friends. It happens. It has always happened. Recall William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer starting a war to sell papers? For a more recent example, consider Rupert Murdoch’s Fox News Network and the goosing of television ratings to boost advertising revenues by splattering the international airwaves with bogus claims that Saddam Hussein was responsible for 9/11. Fox, and The New York Times’ Judith Miller, reported that he also possessed weapons of mass destruction, which he did not.

Early on, in ploughing the rocky fields of journalism, I realized the most interesting events that were never covered involved news about news organizations themselves. My epiphany came with my inaugural executive job as editor of a group of suburban newspapers in South Florida, owned by Knight-Ridder, which also published the massive Miami Herald. My multiple layers of bosses included both journalists and business execs, who uniformly assured me that I would have “absolute freedom” in editorial matters. I was skeptical, but, heck I had already been welcomed into the Herald’s executive dining room—and been given Knight-Ridder stock options.

Yet, I had barely settled in my office before I got a call from a business executive, who I recall saying: “You know those state legislative elections coming up? Go ahead and endorse whichever candidates you want—except you can’t endorse Joe Gersten.” I asked why Gersten—a name I’d never heard before—was considered anathema.

It was not something I should trouble myself about, he told me.

Media bosses manipulate news—fabricate, distort or bury information—to benefit themselves or their friends. It happens. It has always happened. Recall William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer starting a war to sell papers?

I learned later that Gersten’s dad was a labor lawyer who had defended newspaper unions during bitter, protracted disputes with the Miami Herald in the 1950s. I endorsed the brilliant but acerbic Gersten anyway. To me, he was by far the best choice among the legislative candidates. I thought the ax would fall on my young neck, but I was apparently saved by the true journalists among my bosses.

I was later asked by a journalism watchdog organization to track 108 legislative stories over a yearlong span involving the same Joe Gersten. Whenever an article about Gersten—say, written by The Associated Press or another Florida news outlet—was “positive,” that same story would be recast by the Herald with the most negative spin possible. Why? Knight-Ridder was infamous for destroying newspaper unions—even dispatching teams of strikebreakers to assist other publishers with their labor disputes. And, with almost biblical vengeance, the Herald would punish people such as the Gersten clan. Its retribution often extended over generations.

Gersten would later get into a political smackdown with the most sacred of sacred cows in Miami: Janet Reno, the local state attorney who was then on her way to becoming U.S. attorney general under Bill Clinton. Her father was a former Herald reporter, her mother a writer at the afternoon Miami News. She had demigod status when she visited 1 Herald Plaza, the building that housed both newspapers.

Freedom was mostly alone in connecting the dots on major aspects of the story, primarily concerning the sources of an avalanche of prescription painkillers.

In 2000, an award-winning Australian journalist, John MacGregor, and I teamed up to investigate Reno and her attempts to demolish Gersten. In May, 2001, after a year of investigation, we reported that Reno betrayed her offices and used her power corruptly to crush an opponent. Backing up our assertions of a conspiracy was a congressional report issued April 10, 2001. You’re not likely to read about this damning appraisal of Reno. Or, if you do, you’ll find that the Florida press immediately circled the wagons around Reno. The story was frightening. Scarier yet was the collusion in this debacle by the Miami Herald.

Reno first targeted Gersten when he was running for Florida attorney general—and the Herald, hating that idea, suggested she seek the office herself. Reno didn’t run. But Gersten lost to another Herald vassal. Gersten then became a Dade County commissioner—and by 1992 was well on his way to winning the job of county mayor.

Until, that is, Reno and the incumbent mayor of Dade set about to frame Gersten for smoking cocaine at a crackhouse, cavorting with hookers and, even, murdering a transvestite prostitute. There was no tangible evidence—no fingerprints at the crackhouse, and Gersten’s drug tests were negative. But Reno created a perjury trap for him—Gersten could admit the crimes or one of the lowlifes would testify that Gersten lied, and he’d be indicted for perjury. Either way, his career would crash. On vacation in Australia, Gersten decided to stay Down Under. “I looked at the forces against me and they were just too powerful,” he told me then.

A U.S. congressional committee investigating Reno issued a 26-page report on the Gersten affair, concluding that Reno and her allies “participated in a conspiracy to make allegations that they knew to be false. … Some of those who had made allegations against Gersten had themselves been subsequently indicted.”

Without ever detailing most of the evidence in the congressional report, the Herald did its damnedest to dismiss the findings. Most of the newspaper’s “news” accounts lauded Gersten’s tormentors. A Herald “analysis” refers to Reno as “Janet.” Gersten remained just Gersten, except where the writer derided him as “poor Joe.”

Finally, a Herald editorial snickered derisively that Gersten’s defense was “silly.”

Congressional investigators didn’t believe Gersten’s case was silly. And Australian authorities discovered what they called the “X-files”—documents that made clear that Reno, while U.S. attorney general, illegally used the FBI to spread falsehoods about Gersten in his newly adopted home. The Wall Street Journal broke from the media pack and termed Reno’s jihad “Gerstengate.”

But Reno’s cheerleaders at the Herald never investigated what is now well documented. Their refusal is testimony to both the power and depravity of the press.

Seventeen years later—and there’s ample irony here—Knight-Ridder no longer exists, the Herald is on life support, Reno is dead, her legacy besmirched by her underlings’ lethal siege of the Branch Davidians in Waco, the predawn grab of Cuban child Elian Gonzalez and more. Gersten, meanwhile, became a formidable barrister in both Australia and Ireland.

The moral of Gerstengate?

“News” is not a passive commodity. It can be weaponized. “Fake” news can be created. People’s lives can be destroyed. And skulking behind much of that are corporate media owners whose missions are written in dollar signs.

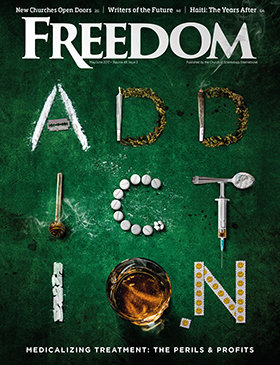

Here’s another example: Two years ago, Freedom carried a cover story on the “opioid epidemic.” We return to that issue in this edition, and originally began reporting on it as early as the 1980s.

Freedom was mostly alone in connecting the dots on major aspects of the story, primarily concerning the sources of an avalanche of prescription painkillers. In roughly a thousand articles on a news database about the epidemic, there were only 28 hits that include “opioid,” “epidemic” and—this is key—the “Sackler” family—owners of Purdue Pharma, which did more to turn Americans into addicts than any Mexican or Colombian cartel. Purdue used networks of doctors to push the highly toxic OxyContin—like drug kingpins using street-corner kids to distribute narcotics. Yet, the media put on blinders concerning the Sacklers.

As finances of newspapers and broadcasters collapsed in recent years, many of the remaining ad dollars have come from aggressive promotion of drugs by pharmaceutical companies. Newspapers and TV stations understand this reality: They’re focused not on the public good, but on not biting the hand that feeds them.

Equally devastating are other painkilling pills being pushed by people in white lab coats. The devil’s brew of opioid painkillers should have been a focus long ago for daily newspapers and news broadcasts. But only recently have they begun to tell those stories abundantly, and only after the plague became so obvious it couldn’t be ignored.

There’s one thing Big Pharma has that cartel drug lords don’t: massive advertising budgets. The drug companies spent about $6.4 billion in 2016 on pitches to consumers. And they pushed five or six times that amount into the pockets of doctors for “marketing,” which in any ethical universe would be spelled “bribery.”

No memo had gone out to newsrooms across America saying, “Go soft on reporting the opioid epidemic, and whatever you do don’t depict Big Pharma as craven pushers.”

But that message guided media moguls nonetheless. As finances of newspapers and broadcasters collapsed in recent years, many of the remaining ad dollars have come from aggressive promotion of drugs by pharmaceutical companies. Newspapers and TV stations understand this reality: They’re focused not on the public good, but on not biting the hand that feeds them. Where are the ethics in that?

John F. Sugg is Freedom’s Florida-based senior editor.