Over the 2024–25 financial year that ended June 30, the Australian Federal Police (AFP) logged 420 reports of exploitation—each one a story of coercion, deception or control—marking a 10 percent increase from the previous year’s 382.

Among the sharpest spikes was a crime most Australians have never heard of: exit trafficking. Legally defined as the use of coercion, threats or deception to make—or attempt to make—a person leave Australia, it often overlaps with domestic or family abuse rather than organized crime. The motive usually isn’t profit but control: Partners or relatives may deceive victims into traveling overseas, then withhold passports or consent for children’s documents to stop them returning. In a single year, such reports more than doubled—leaping from 35 to 75 cases—and more than nine in 10 victims were women.

What begins as family or relationship abuse in Australia can become a form of exile abroad.

Other forms of exploitation also rose—with forced marriage climbing from 91 to 118 reports and sexual servitude from 59 to 84.

For all the shock in those numbers, the significance lies beneath the surface. Modern slavery and trafficking are among the least visible yet most pernicious crimes in society. Many victims remain confined or too fearful—or deceived—to speak, according to the AFP, which notes that trafficking indicators often include inability to communicate freely, fear or anxiety and lack of control over earnings or identity documents.

The AFP describes the dramatic surge in exit trafficking—with a consistent increase in forced marriages—as “just the tip of the iceberg.” By illuminating this rise, the data underscore that awareness programs and reporting mechanisms, while essential, continue to chase a much larger shadow: the hidden scale of abuse and the enduring barriers that keep victims from coming forward.

Exit trafficking’s climb is especially disturbing not just for its rate of growth, but for what it symbolizes: the extension of domestic coercion across borders. Under Australian law, “trafficking” includes coercing, deceiving or threatening a person to move them into, within or out of Australia—regardless of whether or not any profit was involved. So what begins as family or relationship abuse in Australia can become a form of exile abroad, where victims are cut off from support, legal protection and sometimes even their own children. In that sense, exit trafficking blurs the line between private violence and transnational crime—showing how control itself can become a form of trafficking.

A particularly telling account of such exploitation was recently published on SBS Urdu, an Australia-based multi-platform media organization devoted to programming and digital offerings for dozens of immigrant communities in the nation. The story recounts one woman—identified by her pseudonym, Fatima—who was stranded in Pakistan with her children after her husband returned to Australia and refused to renew their passports. She described contacting the Australian High Commission and other agencies without meaningful assistance. Domestic violence advocates report similar patterns, particularly in migrant communities where offenders misuse family authority—for instance, by controlling passports or refusing consent for children’s travel.

In another troubling sign, forced marriage—often overlooked in popular narratives of trafficking—continued its upward trajectory. The jump from 91 to 118 reports suggests that pressures to marry, sometimes coercively, remain stubbornly entrenched. The AFP links this rise in part to growing community trust in reporting mechanisms.

That said, not all trafficking types rose. Forced labor reports fell from 69 to 42, and cases of deceptive recruiting dropped to just five. Analysts at the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) caution that the figures collected through official channels represent only victims identified and recorded by participating agencies, warning that variations in reported cases may reflect differences in detection or access to services rather than true prevalence. But even with those limitations, the institute’s pilot study—the Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery National Minimum Dataset—offers rare insight into the nature of exploitation itself, showing that it cuts across industries and that many alleged offenders share close personal ties with their victims, often as partners or family members.

Australia stands at a crossroads.

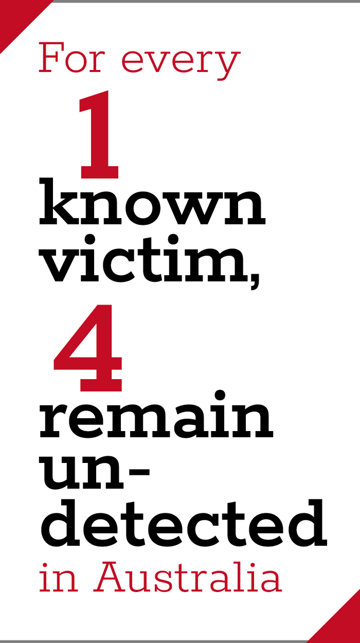

Australia is widely considered to have a relatively low prevalence of modern slavery compared to many nations—a 2023 estimate placed about 41,000 people living in slavery or slavery-like conditions (a rate of 1.6 per 1,000) in 2021. Yet official reports capture only a fraction of that total. Analyses by the AIC suggest that for every known victim-survivor, roughly four others go undetected. The barriers are many: Victims may not perceive themselves as such, or they may fear retaliation or exposure, face language or visa constraints or distrust authorities—especially when the perpetrators are known to them.

Moreover, the Modern Slavery Act 2018 compels large entities to issue annual statements about supply chain risks—that is, the potential for exploitation within the production, sourcing or delivery of goods and services. But critics argue enforcement is weak, and many corporate responses remain largely symbolic.

That weakness reflects a broader challenge: the gap between legislative ambition and on-the-ground capacity. Human Rights Commissioner Lorraine Finlay has welcomed the creation of an Anti-Slavery Commissioner but warns that major reforms already endorsed by government still await full implementation.

At the same time, the human services sector remains a critical anchor for victim support. The Australian Red Cross offers the Support for Trafficked People Program, a key pathway to safety and assistance, while the Forced Marriage Specialist Support Program allows those at risk to seek help without first involving police.

On the prevention and awareness front, the AFP’s Human Exploitation Community Officer initiative has become a cornerstone of outreach: In 2024–25, officers delivered more than 220 presentations and held over 700 community and institutional engagements.

From a governance standpoint, the Modern Slavery Amendment Act 2024, which established the independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, created a statutory office to monitor, report and promote anti-trafficking efforts. In August 2025, the government appointed career diplomat Jane Duke as Ambassador to Counter Modern Slavery, People Smuggling and Human Trafficking. Foreign Minister Penny Wong said Duke’s role signaled Australia’s commitment to regional collaboration through the Bali Process, a forum that unites Asia-Pacific governments in confronting people smuggling, human trafficking and related transnational crimes.

Internationally, Australia’s progress has drawn praise: The US State Department’s 2025 Trafficking in Persons Report ranked the country in Tier One again, citing strong governmental action against trafficking. Yet the report and local experts alike warn of unfinished work. Justine Nolan, director of the Australian Human Rights Institute and a law professor at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, described ongoing “incoherence between legislative approaches, business practices and the demands of stakeholders.”

Australia stands at a crossroads: The record numbers may reflect more courageous reporting—but they also reveal exploiters adapting to new vulnerabilities. The state, civil society and the public must now respond with equal agility. The real test will be whether next year brings fewer victims—or merely more reports.