And deadly.

It’s the darknet, an online marketplace where illicit substances are bought and sold through specialized software that keeps both buyers and sellers anonymous. With just a click, drug users anywhere in the world can order narcotics—no face-to-face contact required.

This digital bazaar mimics the familiar trappings of legitimate e-commerce: shopping carts, advertisements, sales promotions, even customer reviews. Its chief allure for criminals is its veil of anonymity, shielding transactions from traditional search engines. Like invisible ink in cyberspace, the darknet is untraceable and foolproof.

Until now.

“It’s not like when you’re dealing with your local neighborhood dealer.”

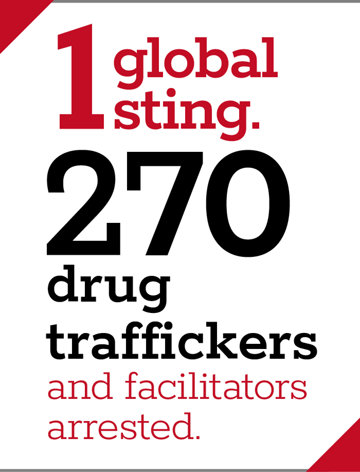

Like something out of a techno-thriller movie plot, a coordinated, global multi-agency operation on four continents targeted darknet drug trafficking. Code-named RapTor, the law enforcement action whose results were announced last month netted drug vendors, buyers and administrators—arresting 270 and seizing over 317 pounds of fentanyl or fentanyl-laced narcotics.

Up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times more powerful than morphine, fentanyl is the leading cause of overdose deaths in the US. Just 2 milligrams—the equivalent of about a dozen grains of table salt—is considered lethal, and one kilogram alone has the potential to kill 500,000 people, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration. That means RapTor seized enough fentanyl to kill 71.5 million people.

The large-scale investigation involved 12 federal agencies and international partners from Austria, Brazil, France, Germany, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland and the UK. The operation’s success pivoted on the work of FBI’s JCODE (Joint Criminal Opioid Darknet Enforcement), which targets darknet distribution of illegal opioids.

“It’s not like when you’re dealing with your local neighborhood dealer or even a cartel member,” said Aaron Pinder, unit chief of the Hi-Tech Organized Crime Unit at FBI Headquarters, which runs JCODE. “The darknet vendors that we investigate, they truly operate on a global scale in their ability to reach and sell drugs to customers out there.”

“One of the things that makes a darknet marketplace so dangerous in the eyes of law enforcement is the fact that it’s such an easy-to-use platform,” said Katie Brenden, an analyst on the JCODE team. “There’s a lot that is put into place that makes it appear to be legitimate, when what’s really happening is there are people in garages or basements that are using pill presses to make their own pills and sell them online across the country and sometimes across the world.”

A buyer, then, who thinks he’s purchasing Substance A on the darknet may unwittingly imbibe something entirely different—likely something laced with fentanyl. That could mean a deadly dose.

“The FBI mission statement is to protect the American people and uphold the Constitution,” Pinder said. “And that’s ultimately what JCODE is about. We have become very adept at identifying the individuals behind these marketplaces, no matter what role they’re in, whether they’re an administrator or a vendor, a money launderer or indeed a buyer.”

RapTor sends a clear message to criminals hiding behind the anonymity of the darknet that their digital hiding places aren’t safe any longer.

Another key mission of JCODE is educating people about the risks involved in purchasing darknet drugs.

But why stop at the darknet? Risks, colossal risks, are involved no matter where or how a dangerous substance is procured. Be it the darknet, a dark alley or a dark corner of your child’s playground, drugs are dangerous. Period.

With effective education, demand goes down. Foundation for a Drug-Free World’s Truth About Drugs is the model for such an awareness campaign. Sponsored by the Church of Scientology, the global initiative has already reached over 1 billion people and is used by over 1,000 law enforcement agencies across the globe.

The goal is simple. As Pinder says, “We’re trying to keep people safe.”