Its symptoms include nightmares, diarrhea, vomiting and “brain zaps,” as well as vertigo, tremor, insomnia, panic, frequent and intense outbursts of anger and suicide. The symptoms can last from 1.5 months to nearly 14 years if they don’t end your life before then.

One study found PAWS afflicts 15 percent of those coming off of antidepressants.

This is the hell experienced by those who dare to come off their antidepressants, a hell to which so many are frequently condemned that it now has an acronym and a name: Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS).

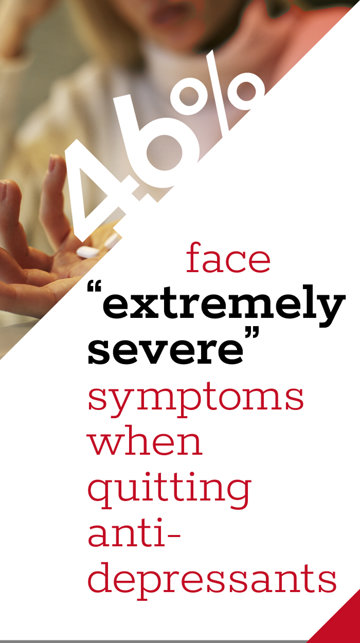

One study found PAWS afflicts 15 percent of those coming off of antidepressants. Meanwhile, 46 percent of those withdrawing from antidepressants rated their symptoms as “extremely severe.”

Researchers from Switzerland’s Zurich University of Applied Sciences and Kalaidos University of Applied Sciences studied PAWS and published their findings in the journal Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences in May. They aimed to examine the severity and prevalence of the condition, as well as any potential remedies. Their task was twofold: (a) review existing research and (b) synthesize the findings.

What they found was a disheartening vacuum of data—just seven papers investigating PAWS, most of which were limited in scope and had methodological failings, raising more questions than they answered.

“Compared to the steadily increasing number of editorials, commentaries and narrative reviews mentioning PAWS, the lack of high-quality original studies providing reliable evidence on the epidemiology and clinical management of PAWS is striking,” they wrote.

Moreover, the bulk of the research was derived from a few case reports and analyses of accounts posted online by individuals reaching out for help with severe withdrawal symptoms.

So, where are all the case histories? Certainly, with 11.4 percent of adult Americans on antidepressants—and with 46 percent of those coming off of them experiencing everything from “brain zaps” to suicide—there must be somebody somewhere keeping a precise record of persistent withdrawal symptoms. On the other hand, that would assume that the psychiatrists diagnosing and the drug manufacturers dispensing antidepressants actually care about their patients.

Do they?

To answer that, one need only examine the lethal side effects of these drugs—including violence, aggression and suicide—for the millions currently prescribed them as a “cure” for everything from learning difficulties to bedwetting, drug addiction to fear, criminality to premenstrual stress.

Or, if one has the stomach for it, one can look into the at least 39 school shootings and school-related acts of violence committed by those taking or withdrawing from psychiatric drugs, resulting in 200 wounded and 100 killed. And those are only the ones we know about. In other instances, the psychiatric drug history of the shooter was neither confirmed nor denied, with no information made available—something like what the Zurich and Kalaidos researchers ran into in their fruitless search for data about PAWS: a big blank wall hiding something ugly and reeking of death.

Possibly, the frustrated Swiss mavens would be wiser to gear their investigatory skills not to what happens to people who stop taking those drugs, but rather to why so many are so desperate to stop taking them in the first place.

There is plenty of evidence for that.