As such, it has become a place of honored glory—hallowed ground.

The man who once had his office nearby was also a highly unlikely candidate for honor and heroism: Oskar Schindler, a Nazi, a womanizer, a black-market criminal, a habitual drunkard and a crooked businessman who profited from slave labor and war.

“Everybody said there was nothing I could do. And that’s a lie because there is always something you can do.”

And yet, Schindler became a savior of Jews. To them he was a revered angel and a rescuer from their certain deaths. He was also the subject of the 1993 movie Schindler’s List, honored as “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial institution to the victims of the Holocaust. When Schindler died in 1974, he was the only former Nazi buried on Mount Zion in Jerusalem.

And now, Schindler and his former factory in the Czech Republic’s Brněnec are being remembered with a new museum, the Museum of Survivors, that held its grand opening on the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II.

It was from this factory that the “Schindlerjuden,” or Schindler Jews, were sheltered and kept from the death camps through Schindler’s bribery and other trickery, like maintaining a false “friendship” with Amon Göth, the murderous commandant of the Kraków-Płaszów concentration camp in German-occupied Poland, who was ultimately hanged for his terrible war crimes.

Daniel Löw-Beer is the grandson of the last Jewish family that owned the building and operated it as a textile factory since 1854, but the Germans took the factory over when they occupied the Czech Republic.

Löw-Beer became a major supporter of the museum plan and said at the dedication ceremony that his family fled for their lives from the Nazi invasion. Of the village of Brněnec, he said, “My grandfather lived here, my father lived here and then the world was shattered one day in 1938.

“It’s a universal place of survivors. We want those stories to be told.”

Schindler operated the plant, from which he duped the Nazis into believing his Jewish workers were producing artillery shells to help the war effort. This, in turn, kept the Nazis from closing the place down and shipping its workers off to the gas chambers.

After the war, the factory operated until 2009, making textiles for Ikea and Skoda car seat covers, before the Shoah and Oskar Schindler Memorial Endowment Foundation obtained the facility.

Jaroslav Novak, a writer and long-time supporter of the factory’s renovation, said: “This is the only Nazi concentration camp in the Czech Republic that is still standing in its original building. You cannot allow it and the whole history of Schindler to disappear.”

“Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.”

The jarring contrast between a site once designated a labor camp and the near-sacred memorial it later became, and a man like Schindler—of highly questionable morality at best—becoming idolized as a savior, a rescuer, a knight in shining armor, has not gone unnoticed.

Was Schindler a saint, or a sinner … or both?

“Yes, Schindler was a Nazi, a war criminal and a spy,” Czech historian Radoslav Fikejz said, “but I have met 150 Jews who were on his list and were in the Brněnec camp and they say that what’s important is that they are alive.”

In one of Schindler’s most remarkable rescues, some 300 Jewish women—his workers who had been mistakenly deported to Auschwitz—were freed through his intervention. According to Vashem, it was the only known instance during which such a large group was allowed to leave Auschwitz alive while the gas chambers were still operating.

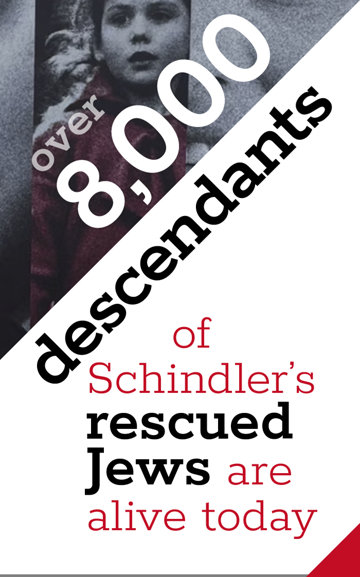

There are plans for a complete renovation of the entire factory, which is only partially completed now. The Arks Foundation, which called the building “Schindler’s Ark,” wants to restore Schindler’s office and several other buildings on the site—a tribute to a man whose actions helped ensure over 8,000 descendants of those he saved are alive today around the world. Without Schindler, none of them would have ever existed.

Schindler’s wife, Emilie, who was also involved in saving Jews in the war, died in 2001 at the age of 93.

“Oskar and Emilie Schindler are proof that one person can make a difference,” said Rena Finder, one of Schindler’s rescued Jews. “Everybody said there was nothing I could do. And that’s a lie because there is always something you can do.”

The Jews he saved gave him a gold ring in 1945, made from gold teeth of the survivors, and inscribed with the message, “Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.”

For all his faults, in the end, Oskar Schindler picked his side, took his risks and did something uncharacteristic—something very dangerous, very human, very admirable and kind—and became a man who earned his rightful place of respect in history.