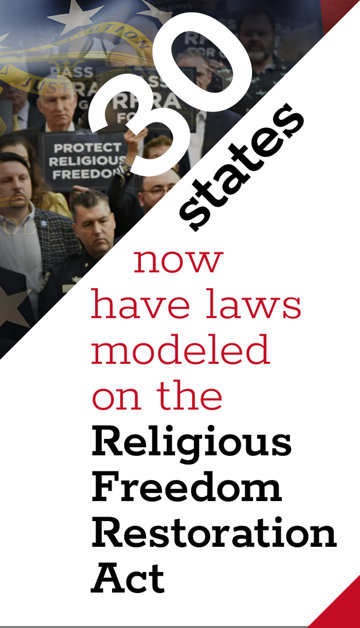

Putting an exclamation point to that freedom, state after state has been enacting its own version, mirroring the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993.

And last month, Georgia Governor Brian Kemp signed Senate Bill 36 into law, making the Peach State the 30th to enact such a measure, and the second in two months (Wyoming passed its own version on March 6). The new RFRA limits government interference with religious practices unless there is a compelling interest to intervene.

“Every Georgian should be free to exercise their faith without unfair federal, state and local government intrusion.”

Specifically, Georgia’s new law protects the right of individuals to practice their faith free from undue government interference. It empowers citizens to challenge any government action that imposes a substantial burden on their religious exercise, unless the state can demonstrate that the action serves a compelling interest and is the least restrictive means of achieving it.

The law adopts a broad definition of “exercise of religion,” applies to all levels of state and local government and provides individuals the right to seek judicial relief—including recovery of attorney’s fees—when their religious freedoms are infringed upon. The law upholds the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause and preserves the ability of government to support religious organizations where constitutionally permissible.

“Every Georgian should be free to exercise their faith without unfair federal, state and local government intrusion,” said State Senator Ed Setzler, the bill’s sponsor, adding that the bill “protects ordinary people” from such intrusion.

The bill, however, did not pass into law unopposed. Georgia is one of only three states with no comprehensive civil rights or anti-discrimination law soldered into its legal codes, meaning it does not legally prohibit discrimination by businesses like retail stores, hotels, doctors’ offices and restaurants based on race, gender, ancestry or religion.

Some dissenting lawmakers argued that the lack of protections could allow the new RFRA to be used against minority religious communities, rather than promoting equal religious freedom for all.

As Muslim lawmaker Ruwa Romman explained: “What if a Muslim woman who wears a headscarf is in a workplace and her boss decides to fire her because it offends his faith? What if, for example, somebody is praying—takes five minutes to pray during the day—and their boss says, ‘You know what, you don’t believe in Jesus Christ as your Lord and Savior, and I’m going to fire you. It is my business, I should be able to do that.’ … To me, the negatives far outweigh any potential benefits [of the law].”

Georgia’s only Jewish lawmaker, Rep. Esther Panitch, warned that the law could also open the door to discrimination against Jews. Courts, she said, would be burdened. “Each case will require an extensive analysis of whether antisemitic expression is truly motivated by sincere religious beliefs. The result is that secular antisemitism faces consequences while religiously motivated antisemitism receives protections.”

It was largely because of Georgia’s lack of civil protections that a similar law was vetoed by then-Governor Nathan Deal in 2016 in response to widespread protests and the worry from businesses that the law would hurt tourism and discourage prospective employees. This year’s bill was likewise opposed by the Atlanta Chamber of Commerce.

Rep. Deborah Silcox tried to add an anti-discrimination measure to the bill in an attempt to close that perceived loophole, but failed in the end. Rep. Panitch, who voted for Silcox’s amendment, said, “This is a license to discriminate. You have to ask yourself: Why won’t they incorporate anti-discrimination provisions if they say that they’re not going to discriminate?”

In defense of the measure, Rep. Tyler Paul Smith, who presented the bill in the House, said: “This is not a license of private citizens to discriminate against private citizens. This prohibits the government from burning religious exercise in our state.”

Addressing the concerns of those wary of the bill, Governor Kemp said: “I have always maintained that I would support and sign a version of RFRA which mirrors the language and protections provided by federal law since 1993. My commitment to that promise and to the deeply held beliefs of Georgians of faith remains unwavering. I also want to assure those of differing views that Georgia remains a welcoming place to live, work and raise a family.”

Several policy think tanks have weighed in.

“Right now, Georgia has a glaring gap in its protection of a fundamental First Amendment right—religious freedom,” said Taylor Hawkins of the 1st Amendment Partnership. “The Religious Freedom Restoration Act by State Senator Ed Setzler simply restores those protections to their original intent, placing them on equal footing with freedom of speech and other fundamental rights.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Georgia, for its part, warned that the bill “jeopardizes the rights of minorities.… Religion could be cited to deny housing, healthcare and equal pay to Black people, women, interracial couples and others. It historically has been.”

It seems that each bend of Dr. King’s arc of the moral universe toward justice contains a teaspoon or more of “But what if...” That may be the risk that comes with each step taken toward greater freedom. But nothing worth fighting for comes without risk.

Thirty states have decided that risk is worth taking.